(Telegraph Magazine, Oct 21, 2006)

The Bafta-winning filmmaker Dominic Savage, chronicler of society’s margins, has turned his lens on the plight of Britain’s homeless. Photographs by Manuel Harlan

The first film for television that I made was a documentary about my father called Seaside Organist.I always admired my father. He would entertain on the Hammond organ between May and September each summer, playing three sessions a day—morning, afternoon and evening—year after year for 40-odd years, at a pleasure complex called the Lido in Margate. What I saw him do all those years was provide pure entertainment—it was all about community. People who came on holiday were working people from the industrial towns and cities of the country. He would play music and songs that took them away from reality, that allowed them to dream.

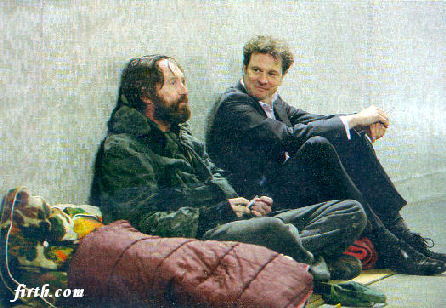

Colin

Firth, who plays a conscience-stricken hedge-fund manager,

with Pierce Quigley as a beggar, in between takes. |

What my films do is, in a way, the

opposite; they are about confronting life’s realities, not escaping

them. My first drama, Nice Girl

(2000), was about the break-up of a young marriage and the impact on

the children, basically a film about getting married too young. When I Was Twelve (2001) dealt with

the issue of children who run away from home. Out of Control (2002) was about

young offenders, and Love + Hate

(2005), my first cinema feature, was about race and bigotry. They are

all films about people in difficulty, who are on the outside of

systems. That is where, I think, great drama comes from. I have always been curious about people: where they are from, what they think, how they live, how their lives differ, what they care about. Maybe it is because of all those people I saw as a child, coming and going on holiday in Margate, and not really knowing anything about their lives, but always wanting to. |

My inspiration to be a director was Stanley Kubrick. My father had encouraged me to play the organ, and from the age of eight I would play a couple of tunes during one of his programmes—12th Street Rag and When the Saints Go Marching In. My feet couldn’t really touch the pedals, so I used to virtually stand and play. It pleased the audiences. It was a novelty. I used to get 10p thrust into my hand afterwards, which I would spend in the arcades. (Later on, when I was a student, I would spend the summers playing the morning session on the organ using the same programme of songs as my father.) Because of my playing and performing, I got a part in a TV special playing the piano for Barbra Streisand in 1974. That led to child acting roles, and then, aged 11, to a part in Kubrick’s film Barry Lyndon.

This was a life-changing event for me; I found Kubrick’s presence immense. At the time I didn’t know who he was, and certainly hadn’t seen any of his films, but his intellect and the way in which he made films deeply impressed me. He was open and curious, always experimenting, constantly changing things for something more interesting.

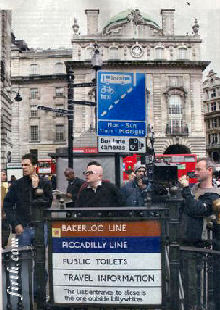

Dominic

Savage and crew filming Born Equal in Piccadilly Circus

|

I remember I had been on

call for some weeks before my first scene was filmed, so my

anticipation was high. The set was ready and Stanley wanted to rehearse

the scene. It was incredibly daunting. In this very grand room in

Dublin Castle, meticulously lit by thousands of candles in chandeliers,

Marisa Berenson and I, in full costume and make-up, walked it through.

(I played her son in the film.) Stanley took one look at it through his

viewfinder and decided it wasn’t right. That left a very strong impression on me; it was not an easy choice, and obviously had a cost implication, but he couldn’t film the scene he wanted; for whatever reason the place wasn’t feeling or looking right to him, so he abandoned it. I like to think that I do similar things; if a scene doesn’t feel right I will either abandon it or change it to some other location where it might feel better. An example of this is a sequence in my new film Born Equal that involves a day trip to the seaside. I had always written it as being Southend, consciously trying to avoid my hometown Margate. It was always scheduled to be filmed in Southend. The day before we were due to go, I felt wrong about it. How could I deny the fact that I had written the scene because of Margate and my strange romantic attachment to the place. I knew I had to go there. Even though it was a nightmare to re-organise, we did. For me it made all the difference. It brought an extra poignancy to the scene. |

As different as our methods and our films are, I think Kubrick and I share a similar independent spirit about creating a film. I knew after the experience of Barry Lyndon that I wanted to do what he did, and certainly not act.

I discovered my abilities at the National Film School. Through making documentaries I realised that what I really enjoyed doing was engaging with people, and I discovered over time that I was able to get to the truth of someone, and that they revealed things about themselves to me that were personal, unique and insightful.

| For me the vital element for

creating a film is this connection with people. It is the research from

real life that becomes the inspiration for the script. I start a

project with a completely open mind about what the film will be about.

I don’t rush at things, and don’t make up my mind immediately. I try to

meet as many people as I can, as it is from those people that a story

starts to form. With Born Equal it started with the premise of a film about homelessness today. I was struck by the number of people living in temporary accommodation due to an affordable-housing shortage. At present there are more than 100,000 households stuck in this situation. I did a tour of temporary hostels around the country, with the specific intention of meeting people who had known a better life, but through circumstance had ended up in a hostel. I was interested in that change of life, how and why people can fall between the cracks. I met and spoke with many people, at least 50. I would sit in their rooms and hear their conversations. Even though I had a Walkman I never recorded the conversations—it seemed insensitive. It was the memories of those meetings that became important for me, the feelings I got from those people. What came across to me strongly was not so much the grim conditions and the psychological effects of not having your own home—as bad as that is—but the reasons why people had found themselves in this situation, which as I saw it could just as easily happen to me, and many others like me. It doesn’t take much, just a series of unfortunate events—relationship breakdown, illness, losing a job—to tip one’s life into a descent, and once you are in that situation it’s really hard to get out of it. |

Anne Marie Duff is attended to by a member of the production crew |

The people I met were very ready to talk about their lives—maybe it was a way of unburdening themselves. I always remember the stories people tell me, and how it affected me when I heard them and use that when I am writing the characters and themes in a film.

There is always a point when through someone I meet I am so moved that I know I have to make this film. There was a woman in a B&B in Scarborough who had had a comfortable life. She had a three-year-old and was expecting another shortly. She had escaped from domestic violence, preferring the idea of having nothing rather than enduring a life of violence. She was lost and numb; she had no one, and no one to be at the birth. I didn’t know how much worse things could get in life, the fact that all this pain was tied in with the supposed joy of birth. It really set the tone for the film.

When I visited a hostel in Swiss Cottage, London, just round the corner from multi-million-pound homes, themes of inequality started to emerge. Then I knew that I wanted to make a multi-stranded film that compared lives, while showing other people in crisis. I wanted my film to make us all think about the people who are in those situations. If you understood it could happen to you, you might think a little bit more about the people we see around us every day who are living in desperation, hand to mouth.

The next process is forming the story and characters. This is always a mixture of everything—people and stories I have heard, not just recently, but over the years, and a lot of myself: my fixations, paranoias, personal experiences and philosophies. I decided the story of Born Equal was to be about a set of characters connected by a temporary accommodation hostel and the area where the hostel is situated. All of them are in search of something, a decent life, and all of them are in crisis. Robert Carlyle plays Robert, a man out of prison searching for his mother. Dislocated from society, he is trying to escape his past and make a clean start. The hostel is where he meets Michelle (Anne Marie Duff), who is pregnant and has a six-year-old daughter, Danielle (Gemma Barrett). Michelle has escaped domestic violence and in their desperation their relationship offers them some kind of hope. Yemi (David Oyelowo) and Itshe (Nikki Amuka-Bird) are in the hostel having escaped violence in their native Nigeria. They have no money and no home, and a parent in real danger. Meanwhile, Colin Firth plays a wealthy hedge-fund manager who is going through his own crisis. Combining these stories gives a broader picture of the film’s overall themes: the importance money in society, the huge gaps it creates, plus the importance of other people in our lives to make our own complete. The importance of family.

Savage,

with Robert Carlyle, who plays a man

out of prison searching for his mother |

It is through the input, feelings

and real-life experiences of the actors that the characters and final

elements of the stories are really brought to life. With this way of

working, it is a very exposing process, and I believe that because they

put so much of themselves in to Born

Equal, it has made the film special, both in terms of the

process, and the end result. Maybe my approach to filming comes from that sense of being an outsider, because of my background; maybe because my parents both came from poor backgrounds, but improved their lives a little and gave us the opportunity to do something more. I am trying to do that ‘something more’ in my own way, which expresses my need to tell stories that have a meaning, that reflect life, and hopefully make people think about society today. I hope the films that I make might effect some sort of change, even if it is only one person who changes as a result—if I have illuminated an aspect of life, of humanity, to that one person then I have succeeded. Of course I want that to happen to millions. |

The third part of my process is casting. I never think it wise to predetermine who will be right for my film. Part of the casting process is seeing who is up for my kind of way of working, above all who I have a connection, a chemistry, with. Again, all of this is very instinctive. Trust between the director and actors is essential. Ultimately, the way I work is quite uncomplicated. It’s engaging everyone in creating this something that illuminates, uncovers, and offers some insight into humanity and life.

It is through the input, feelings and real-life experiences of the actors that the characters and final elements of the stories are really brought to life. With this way of working, it is a very exposing process, and I believe that because they put so much of themselves in to Born Equal, it has made the film special, both in terms of the process, and the end result.

Maybe my approach to filming comes from that sense of being an outsider, because of my background; maybe because my parents both came from poor backgrounds, but improved their lives a little and gave us the opportunity to do something more. I am trying to do that ‘something more’ in my own way, which expresses my need to tell stories that have a meaning, that reflect life, and hopefully make people think about society today. I hope the films that I make might effect some sort of change, even if it is only one person who changes as a result—if I have illuminated an aspect of life, of humanity, to that one person then I have succeeded. Of course I want that to happen to millions.

At the heart of Born Equal is a love story, albeit one that can’t succeed—I find love and film an enticing combination. With my next film, I want to make a serious romantic love story, because in the end love is the beset thing that we humans have got, or will ever have.

‘Born Equal’ will be shown on BBC1 on November 5

Thanks

to Felicity

|

|||

Click on boots to contact me  |

|||