|

|

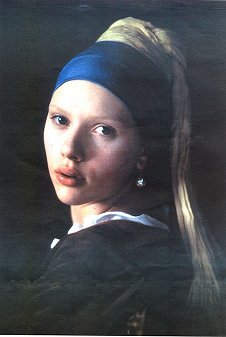

| Who’s That Girl

Peter Webber gets in

Dutch with

his first feature

by Jason Silverman, Telluride Film Watch 2003 The Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer was born in the town of Delft in 1632, and died there in 1675, leaving just 35 paintings and very little else to remember him by. But if a lack of information about Vermeer’s life frustrates art historians—who must wonder what fueled such sublime images—it’s a boon to novelists and filmmakers. In Girl With a Pearl Earring, the best-selling novel by Tracy Chevalier and now a film directed by Peter Webber, Vermeer’s life is given fictive, but convincing, shape. The story follows the creation of one of Vermeer’s best-known paintings, “Girl With a Pearl Earring,” in which a young woman sits, luminous, gazing toward the painter with a look that’s one-part joy, one-part sadness. |

|

| In

her novel, Chevalier posed an answer to one of the art world’s more

intriguing

questions: Who’s that girl? Chevalier called her Griet, imagining her

as

an 17-year-old forced to support her family after the death of her

father.

Coming to work at the Vermeer household, Griet becomes the object of

Johannes’

fascination, and a pawn in the family’s internecine politics.

“Vermeer’s life is a blank canvas,” he said, “which is fantastic for us as filmmakers. Tracy was able to weave a fantasy that incorporates the few things we do know. It’s not a biopic—it’s not the life of Vermeer. It’s about a particularly intense set of relationships that happened within the house where the painting was done.” Webber had been a fan of the painting since studying art history in college. He remembers the first time he saw the work, which hangs at the Mauritshuis Museum in Delft. He was, he said, “moved to tears by its beauty.”

The film held obvious challenges for a first-time director. It’s a period piece, and, told more with gesture than dialogue, demands nuanced performances from its actors. Still, it seemed to Webber to be a good film to start with. “I‘ve wanted to make a movie since I was 15 years old,” he said. “When you get a chance, especially with material like this, you have to seize it. After I read the script, I knew I could do something with it. I felt a sympathy with the material. In England, filmmakers end up in TV because the film industry is so small. TV is filled with people like me desperately hoping that one day they’ll get to make a movie, and I’m lucky that I got to make one. Of course, I’ve put my time in—it wasn’t like I was sitting home and someone knocked on the door and said, ‘Hey, make a movie.’”

“We were lucky enough to get great actors,” Webber said. “But even with great actors, you never can tell whether the sparks will fly, so you have to use your intuition. Sometimes it’s right and sometimes it’s wrong, and in this case it was definitely right. The performances are what make the movie tick. For me, the painting and everything else is background. The most important thing is a middle-aged man’s obsession with a younger girl, a younger girl falling in love with an impressive older man, and the jealousy around the house. It’s a story about power, money and sex.” Webber’s crew included cinematographer Eduardo Serra (Wings of a Dove, Map of the Human Heart, Unbreakable) and production designer Ben van Os, best known for his work with Peter Greenaway. Webber gave Serra and van Os other Dutch paintings from the period as a reference: “We wanted to make sure the whole film didn’t look like a Vermeer,” Webber said.

“You can do all of the technical stuff, but unless it is sparking between your two central characters, you may as well pack up and go home,” Webber said. “No matter how well written the script, no matter now brilliantly lit and shot and decorated the set is, at the end of the day, it’s two people standing there and whether or not you believe and want to follow their story.” |

*Courtesy of Caribou*

|

own website, club, group or community's photo album. Thank you. |

|

|

Click

on boots to contact me |