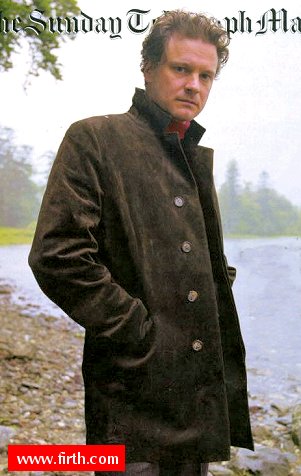

I am no different; I fancy Colin Firth and I am aware that he could well get annoyed about this relentlessly girly, embarrassing swooning. InStyle magazine once asked him whether he minded all the gushing, and he replied that sometimes it is delightful and easy and sometimes it is spooky and weird. The InStyle interviewer also asked him how he liked women to dress; Firth said he thought it was ‘case-specific’. He used the same phrase when I asked him, in a basement room of the Portobello Hotel in Notting Hill, if he minded interviews generally. He said he thought it was ‘case-specific...But, in the end, it is a chat with a person, you know, and it can be quite fun.’ By picking up on the repetition of the phrase, I am not criticising Colin Firth for being wordy or predictable, but I am trying to demonstrate how, especially if you are an actor who is best known for one particular role and in his case, one particular scene—Mr Darcy after an ardour-cooling swim in a lake in the BBC’s 1995 production of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice—you must be asked the same old questions over and over again, and, in the end, you must, possibly subconsciously, adopt an interview voice; an interview phraseology. And Colin Firth is good at giving interviews. He is friendly and courteous, easy on the eye (obviously), tall (6ft 1½ in) and slender, and today dressed in jeans, a striped shirt in muted cheesecloth colours, a navy-blue jacket and RM Williams jodhpur boots. He says he hasn’t always agreed with the way he has been interpreted in interviews but adds that the journalist’s interpretation might be more accurate than his own, which illustrates how easygoing he must really be; willing to question even his own self-knowledge. The reason for this interview is his latest film, Hope Springs, based on New Cardiff, a book by Charles Webb (who also wrote The Graduate). The film is a romantic comedy and Firth says he was pretty determined to play the lead. ‘I was recommended the book by a couple of friends, one of whom was Nick Hornby. [Firth played the lead in the film of Hornby’s semi-autobiographical book, Fever Pitch (1997).] Nick had just reviewed it, and another friend who had read it in similar circumstances sent it to me. And the coincidence was that, while I was thinking, “I must find out who owns the rights to this,” I happened to be working with the very person who did (Barnaby Thompson, a producer with whom Firth worked on The Importance of Being Earnest), so I was in a good position to lobby for the job.’ I meet Colin Firth the day after I have seen Hope Springs and so the film is still fresh in my mind. Also fresh in my mind, because I have been preparing for the interview, are a few of Firth’s other performances: as a cuckold in The English Patient (1996); a modern-day Don Quixote in Donovan Quick (2000); a Nazi official who opposes mass extermination of the Jews in favour of sterilisation in Conspiracy (2001); and an embittered Falklands hero in Tumbledown (1989). They are fine performances, masterful even. But we are here primarily to talk about Hope Springs, not his first romantic comedy—there was Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001) and, of course, Pride and Prejudice—and certainly not his finest. In fact, lingering particularly in my memory is a scene of such saccharine, American-kooky sweetness that if it wouldn’t have been unprofessional to do so, I would have left the screening. The scene involves Firth as an English artist who has traveled to Hope, a small, wacky town in Vermont (think Punxutawney in Groundhog Day), to begin rebuilding his life because he, mistakenly, thinks he has been dumped by his fiancée. In Hope he meets the saccharine one, Heather Graham, who, in order to bed Firth, first gets drunk on peach brandy by glugging from a bottle, then dances like a woodland sprite, naked, in a motel room. She attempts to convince Colin Firth that she has taken her clothes off in order to feel free and innocent, and asks him to do the same. This results in him dropping his trousers, slapstick- style, and many people, particularly Colin Firth fans, may, at this point, wish to leave the cinema. If they stay, however, they will be rewarded by some excellent performances—particularly excellent given the otherwise general awfulness of the film—by not just Colin Firth, but by Mary Steenburgen and Minnie Driver, who plays the manipulative fiancée who turns up in Hope halfway through the film and pours some much-needed acid wit on to Heather Graham’s sugar. ‘I think the construction of the film lent itself to Minnie,’ says Firth. ‘By the time she arrives, you are absolutely gasping for somebody who has that acerbic tone, and I think the threshold of irritation you are taken to, certainly with Mandy (Heather Graham) and me, with my perpetual misery...Have you read the book?’ I haven’t. ‘What appealed to me was the lightness of it—it juxtaposed with a wry cleverness that belied its slightness. It is difficult to explain. Wit is what is going to sell this film, and that is easily obscured in the apparent fluffiness. It sounds like I am hopping about but I remember an Italian saying to me Jane Austen is not “literature”, and that it is not an uncommon perception in Italy. There is an anglophile Italian writer, [Guiseppe di] Lampedusa, who wrote articles about various writers—in their defence a lot of the time—and he was trying to explain why Italians don’t really take an interest in Jane Austen. all her substance is somehow contained in the cleverness of the phrasing. If you undermine that, if you translate it into another language and lose it, you end up with Mills & Boon, and in some ways that brings us back to what I felt about Hope Springs. I am not making a direct comparison with Jane Austen, but there was something in the form of the writing that sold it to me. That if it hadn’t been written so skillfully and so delicately and with such a willful lightness, one would have been left with just a rather banal romantic story.’ I could have picked up on the Italian reference here, and asked him about his wife, an Italian film-producer, Livia Giuggioli. They met in 1995 while making Nostromo (1996) in Colombia, married in Tuscany [sic] in 1997 while being chased by paparazzi, and now divide their time (approximately 70/30, ‘though it varies a lot’) between Islington and Rome and have a two-year-old son, Luca. Instead I ask him about the Anglo-American theme of Hope Springs and whether he has an affinity with Americans given that he also has a 12-year-old son growing up in Los Angeles (from his relationship with the American actress, Meg Tilly. They met while making Valmont [1989] and lived together in a remote part of British Columbia for seven years.) For all his apparent Englishness, Firth has strong connections with America. His mother, Shirley, grew up there, and he spent part of his childhood in St Louis, Missouri, with her and his father, David. They are lecturers who, he says rather proudly, are ‘still working relentlessly, travelling, teaching, learning, conferences, far busier than I ever am.’ Though he says he feels quite American, he also says, ‘I don’t think how you see yourself is necessarily relevant to who you are. People generally, but actors particularly, very often end up becoming representatives of something they are not. If I see a man in tweeds and plus-fours and he is driving an old Jupiter, I’ll think, “You didn’t go to Eton. You didn’t.” In some ways I think I found a niche, and I have been called upon to do variations of that a lot.’ Does he feel that he has ever represented the real Colin Firth in a role? ‘Yeah,’ he says, ‘I suppose it is a bit of a luvvie answer but, yes, all of them to some extent. The whole process is a way of trying to find some common point between this character and yourself.’ In Hope Springs he seems to have been searching for a common point between himself and Hugh Grant. But we can forgive him for that, and if the casting agents don’t seem to see him as he sees himself, then perhaps it is because he is something of a blank canvas. He is like the impressionist who feels obligated to tell you when he has stopped performing—‘and now this is me,’ as Mike Yarwood used to say. The real Colin Firth was born in September, 1960, in Grayshott, Hampshire. He has one brother, the actor Jonathan Firth, and a sister, Kate, who is a voice coach. Colin spent his first four years in Nigeria and then a year in St Louis. Back in England, the Firths moved to Winchester, where Colin went to Montgomery of Alamein Secondary School. He is reported to have been pretty miserable there. ‘Oh God,’ he says, ‘that has been a self-perpetuating thing, which I dare say I was responsible for, my first ever interview as a disgruntled, well, not even disgruntled, just taking my first opportunity to make my first gesture. I only didn’t like school on the level of your average schoolboy not liking school.’ From school he went to Barton Peveril Sixth Form College in nearby Eastleigh; we know this because the Daily Mirror, just as Darcy Fever was climaxing throughout the Western world, dug up a photograph of him with his classmates. He had long hair and was wearing orange flares. By 1983, after three years at the Drama Centre in north London, he had short hair and was wearing cricket whites to play Guy Bennett in Another Country at the Queen’s Theatre. And so he became one in a group of actors who all had their careers launched by Another Country—some in the stage play, some in the film. And some, including Firth, who played Judd the Trotskyite on the screen, were in both. Firth begins to list the others: ‘Another Country has produced Rupert Everett, Daniel Day-Lewis...It was quite extraordinary. For me and Ken [Branagh] it was our first job ever out of drama school. For Dan and Rupert it was the first time anybody noticed them. James Wilby was another—it was his first job out of Rada. Dan took over from Rupert, and I took over from Dan.’ The whole lot of them, of course, took over where Anthony Andrews and Jeremy Irons left off after the mammoth success of Brideshead Revisited. It was a vintage era for handsome young Englishmen in panama hats. Then in 1989 came Tumbledown, in which Firth played Robert Lawrence (a posh James Hewitt-like solider), whose brains are spilled in battled, and who, paralysed, lives to tell the tale and have it acted out by Colin Firth. Lawrence won the Military Cross. Firth was nominated for a Bafta. ‘I find myself thinking back to Tumbledown now,’ says Firth. ‘Some of the guys who worked as background actors were combat veterans, ex-Marines. It was the first time I had heard background stuff that I hadn’t heard in the news, the way soldiers behave under pressure. Things that happen are brutal and ugly and done in he spirit of fear or panic or brutality on any side, and I came away thinking, well, I am just a bloody actors...I think it did kind of do my head in a bit, trying to live this stuff.’ If Firth had been collecting an Oscar last month, would he have felt the need to say something about the war—does he approve of actors making political statements? ‘I would have had to say something. But I do see that there is a danger of being counter-productive, because we are in a paradoxical position. I think everybody who lives comfortably in the West is living a lot of contradictions. If they have got any conscience at all. The only way you cannot be contradictory is if you absolutely don’t give a flying f— what goes on outside your life. That means there is no hypocrisy and no inconsistency, or you just give it up and absolutely devote yourself to sainthood and live a kind of ascetic monastic existence. Otherwise you are compromised, and I have settled for living this bloody compromise. Actors, I think, highlight that contradiction more than anybody else because they are so entrenched in the perception of being utterly trivial and leading this meaningless life which is of no benefit to anybody whatsoever. So we are all in pursuit of self-gratification—earning lots of money and fame—and yet we have this voice, people listen. You can get up on a podium and be watched by half the world. The funny thing is they don’t want to hear you banging on about something that is important, because you have absolutely no credibility.’

Firth say he doubts if I will write about the fair trade issue. ‘I have tried to address this stuff in an interview before, and I said so much stuff that I thought was important, and in the end it was just a rather patronising, dismissive thing about Colin being a bleeding-heart liberal.’ He has researched his chosen campaign well. He says it’s pretty straightforward—‘not controversial... It is just about fair trade. It is about people knowing about it and putting a bloody stop to it.’ He gives me five minutes on how globalisation is supposed to create fair trade but that the rules are in favour of the rich countries. He has the figures— ‘Aid to developing countries by the West is something in the region of $50 billion a year. In order to export the stuff they have tariffs imposed on them—twice as much. It cost them $100 billion a year just...It is an outrageous set-up.’ We are, he says, buying and drinking ‘shit coffee’. The language he uses sounds angry—the ‘flying f— ,’ the ‘bloody compromise’, the ‘shit coffee’—but his voice when he says these things is quite measured, like someone giving a talk. There is a certain bookishness about him. He says he was not a good student at school and he didn’t got to university; something he doesn’t lose sleep over. ‘It is just something that visits every so often. It is a kind of itch that isn’t scratched, and I still feel slight wistfulness around people who did. It is the family legacy really. My father was at Cambridge, his father was at Oxford, my sister went to London, my mother was at Nottingham, and all my cousins and extended family are brilliant achievers in the academic world, and I think there is a part of me that feels a bit like the dunce. But I think life has treated me very, very well, and I have got away with murder, really.’ Murder is a bit strong. Hope Springs isn’t murder exactly, it is just a piece of light, slightly twee, fluffy fun which I am sure Colin Firth will indeed get away with. |

Firth

hasn’t quite settled for living ‘this bloody compromise’, though. He

is,

it turns out, doing his bit and, compared to Sting and Bono and Lenny

Henry,

he is doing it in a rather quiet and dignified way. The première

of Hope Springs tomorrow is a charity premiere for Oxfam, to

raise

money and awareness on the issue of fair trade, and this was instigated

by Firth. ‘I remember being on a protest, a very small one, that was

being

staged on College Green outside Westminster. It was about immigration

detainees’

treatment. There were all these extraordinarily cultivated and highly

informed

activists who had been campaigning for this sort of thing for years—

iercely

articulate, formidable people standing there— and I remember the media

didn’t ask any of them a single question. Instead, they asked what I

thought

I was doing jumping on this campaign. And the answer was right there:

the

press came and only talk to me. So that is the paradox.’

Firth

hasn’t quite settled for living ‘this bloody compromise’, though. He

is,

it turns out, doing his bit and, compared to Sting and Bono and Lenny

Henry,

he is doing it in a rather quiet and dignified way. The première

of Hope Springs tomorrow is a charity premiere for Oxfam, to

raise

money and awareness on the issue of fair trade, and this was instigated

by Firth. ‘I remember being on a protest, a very small one, that was

being

staged on College Green outside Westminster. It was about immigration

detainees’

treatment. There were all these extraordinarily cultivated and highly

informed

activists who had been campaigning for this sort of thing for years—

iercely

articulate, formidable people standing there— and I remember the media

didn’t ask any of them a single question. Instead, they asked what I

thought

I was doing jumping on this campaign. And the answer was right there:

the

press came and only talk to me. So that is the paradox.’