Altered images

Marc Evans'

psychological

thriller Trauma, starring Colin Firth, has found a perfect home in the

Gothic vaults of St Pancras Chambers. The director and star tell Mark

Salisbury how the location affected their vision

|

|

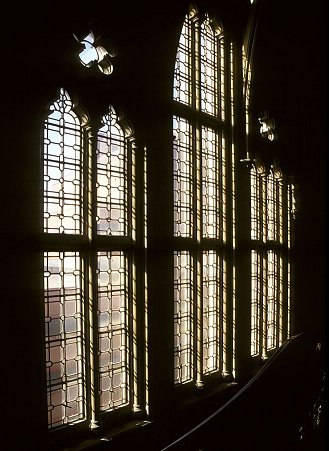

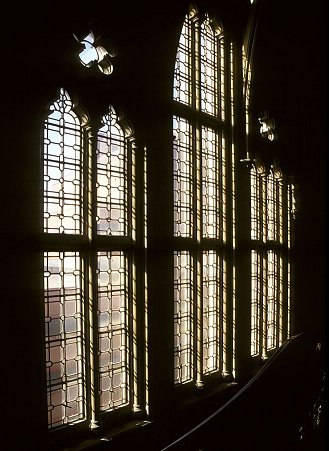

As spooky locations go, St Pancras

Chambers is among the spookiest. With its vaulted ceilings, peeling

wallpaper, long, dim corridors and dank basement, the Victorian Gothic

building—once the Midland Grand hotel, now Grade

I-listed—reeks of must and menace. A perfect

place, in other words, to film a psychological horror chiller such as

Trauma.

Which is why, on a cold morning last June, Colin Firth is skulking the

building's corridors looking more like a tramp than the heartthrob that

Pride and Prejudice made him. Dressed in scruffy jeans and jacket, he

looks dishevelled and downbeat, playing a character who believes he is

haunted by visions of his dead wife (Naomie Harris) who died in the car

crash that he survived. He may also be a murderer, responsible for the

death of a pop star whose body was found washed up in an east London

canal.

Equal parts Don't Look Now, Jacob's Ladder and

Patrick McGrath's Spider, Trauma revolves around Firth's grief-stricken

coma survivor who, attempting to get on with his life, moves into a

flat in a converted hospital and is soon befriended by a neighbour,

Charlotte (Mena Suvari from Americans Pie and Beauty), who is into

crystals and all things spiritual, and who tries to help Ben find some

peace. But as his tenuous grip on reality starts to loosen, we are left

wondering not only about Ben's mental wellbeing, but whether the

ethereal Charlotte may be another figment of his disturbed imagination. Equal parts Don't Look Now, Jacob's Ladder and

Patrick McGrath's Spider, Trauma revolves around Firth's grief-stricken

coma survivor who, attempting to get on with his life, moves into a

flat in a converted hospital and is soon befriended by a neighbour,

Charlotte (Mena Suvari from Americans Pie and Beauty), who is into

crystals and all things spiritual, and who tries to help Ben find some

peace. But as his tenuous grip on reality starts to loosen, we are left

wondering not only about Ben's mental wellbeing, but whether the

ethereal Charlotte may be another figment of his disturbed imagination.

"The beginning of the film is about grief, then changes to being a film

about madness," says Trauma director Marc Evans, who helped start a

mini-revival in British horror cinema with his last film, the inventive

thriller My Little Eye. "It's about loneliness, about someone whose

grief kind of leads them to a kind of madness and a warped perception

of the world."

As the first film to emerge from The Ministry of Fear, the production

company headed by former Edinburgh Film Festival director Lizzie

Frankie, and devoted exclusively to horror—whose slate includes projects penned by

Muriel Gray and novelist Kim Newman—many eyes are on Trauma to see whether

it can deliver. Yet Evans doesn't see Trauma as being a horror movie

per se. "It's definitely in the zone of grown-up psychological

thriller," he says. "It's a film that takes itself seriously. It's not

ironic. It doesn't play jokes with an audience. It starts with a

concept: what if you lost your wife and you woke up on the day that the

world was grieving for a Princess Di or Jill Dando, some kind of

celebrity grief phenomenon?"

"It is

much more about mind games and paranoia and what might be frightening

and what might be menacing," says Firth, during a break in filming.

"There will be a bit of boo as well. It's unashamedly trying to mess

with your mind a bit."

So how does Firth go about playing a man who is not in control of his

senses? "If you're playing a character who can't distinguish reality

from fantasy, you have to use your judgment," he explains. "If

something seems real to you, you have to play it as if it's real. So in

some ways it's perfectly simple. He thinks his wife's dead and then he

sees her; thinks maybe she's alive, but he's not sure. You have to

think yourself into that situation; it can be a fairly freaky thing.

You certainly can't play a thing called madness, because nobody thinks

they're mad."

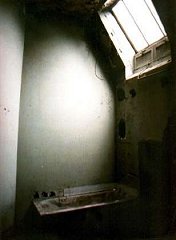

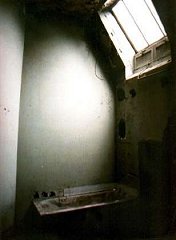

To help realise Trauma's altered sense of perception, and to drive home

the sense of unease, Evans was keen to use odd, unsettling locations

and show a view of London that hadn't been seen of film before. "We

were trying to create a certain idea of Canary Wharf and the City as

this kind of malign, faceless modern East End, and then below that this

kind of Gothic, almost Victorian place where Ben might live. The idea

is he moved into a flat in a converted hospital, and maybe in a strange

way he's never left the hospital during the whole film." Such a place

initially proved difficult to find. "We found a lot of interesting

interiors but I kept feeling we didn't have the scale of, say, the

Dakota Building in Rosemary's Baby."

Evans

eventually found what he was after in one of London's most well known

landmarks—St Pancras Chambers. As the Midland

Grand hotel, which opened in 1876, it had been famed for its then

innovative features, among them its hydraulic, ascending chambers and

revolving doors. Closed as a hotel in 1935, it remained in use as

offices until the 60s when it was listed and saved from demolition,

although it lost its fire certificate in the 80s and has been empty

ever since. Although the exterior was renovated in the mid-90s, the

interior has been seriously neglected - and this has proved popular

with filmmakers, with The Madness Of King George, Richard III and even

the Spice Girls' Wannabe video among those having filmed inside. For

Evans it provided the perfect architectural feature for his film. "We

wanted a really long corridor because all films about people going mad

have got long corridors in them," he laughs. "There's one upstairs 250

feet long." Evans

eventually found what he was after in one of London's most well known

landmarks—St Pancras Chambers. As the Midland

Grand hotel, which opened in 1876, it had been famed for its then

innovative features, among them its hydraulic, ascending chambers and

revolving doors. Closed as a hotel in 1935, it remained in use as

offices until the 60s when it was listed and saved from demolition,

although it lost its fire certificate in the 80s and has been empty

ever since. Although the exterior was renovated in the mid-90s, the

interior has been seriously neglected - and this has proved popular

with filmmakers, with The Madness Of King George, Richard III and even

the Spice Girls' Wannabe video among those having filmed inside. For

Evans it provided the perfect architectural feature for his film. "We

wanted a really long corridor because all films about people going mad

have got long corridors in them," he laughs. "There's one upstairs 250

feet long."

According

to Firth, the building is more than simply a visual metaphor for his

character's descent into madness: its unsettling ambience has even

seeped into his performance. "It's doing all the work today as far as

I'm concerned," he says. "It looks paranoiac, if you light it right. So

in many ways these are my days off. It's very rare that as an actor,

you get any of the stimuli that your character would get, but they've

managed to make the atmosphere so creepy at times." According

to Firth, the building is more than simply a visual metaphor for his

character's descent into madness: its unsettling ambience has even

seeped into his performance. "It's doing all the work today as far as

I'm concerned," he says. "It looks paranoiac, if you light it right. So

in many ways these are my days off. It's very rare that as an actor,

you get any of the stimuli that your character would get, but they've

managed to make the atmosphere so creepy at times."

The

building was always been one of his favourites, Firth admits. "I'd been

dying to get inside. It kind of surpasses expectations because it is

just as kind of gloomy and ghostly as I'd hoped it would be, but is

also more magnificent than I imagined. You can see squares where nasty

paint has been taken off and underneath there's a piece of

extraordinary Edwardian wallpaper." Of plans to renovate the building

as a luxury hotel, he says: "In a way it's almost a pity to do anything

with it. It feels like what it must be like if you could go down on the

Titanic."

For

Firth, Trauma was an opportunity not only to work with Evans again—the pair previously collaborated on the

1994 Ruth Rendell TV adaptation Master Of The Moor—but to shed the labels of period and

romantic comedy, for which he has become synonymous for a while. "It's

the kind of film I love to go and see, and I haven't spent a lot of

time doing the kind of films I love to go and see," he reflects. "There

have been a lot of romantic comedies made, and a lot have come my way,

but I never go to them. This is something that interests me. It

reminded me a little bit of some of the paranoia films that I liked in

the 70s, some of the Polanski films, and things like Don't Look Now." For

Firth, Trauma was an opportunity not only to work with Evans again—the pair previously collaborated on the

1994 Ruth Rendell TV adaptation Master Of The Moor—but to shed the labels of period and

romantic comedy, for which he has become synonymous for a while. "It's

the kind of film I love to go and see, and I haven't spent a lot of

time doing the kind of films I love to go and see," he reflects. "There

have been a lot of romantic comedies made, and a lot have come my way,

but I never go to them. This is something that interests me. It

reminded me a little bit of some of the paranoia films that I liked in

the 70s, some of the Polanski films, and things like Don't Look Now."

Like his star Evans acknowledges the shadow that Don't Look Now, the

Nicolas Roeg classic, casts over Trauma. Both films deal with the

supernatural and the effects of grief. Both films trade in Gothic

menace, a fractured narrative, the use of fragments of colour and

cracked imagery to shock and dislocate. Both films rest on the

reliability of the narrator. But one is a certified classic and the

other is only released this month.

"It's almost as unhelpful as it is helpful to have a film that good as

an influence, but it definitely inspires, to be in that territory,"

Evans says. "I've kind of made myself a rule of never invoking other

directors because you're never going to be as good as them necessarily.

Having said that, it's very hard to have a conversation about genre

films without talking about other genre films. That's the difference

between them and art movies. No self-respecting art moviemaker would

say they were trying to make a Tarkovsky film. Inevitably there are

connections between genre films and there's a kind of British tradition

you can aspire to, [which] Roeg represents par excellence."

It was Evans' unfamiliarity with the genre that made My Little Eye so

refreshing, as he brought an unsullied perspective to a well-worn

formula, and made himself something of a star in the horror field as a

result. So even if Evans doesn't see Trauma as a horror film, that is

how it is going to be perceived. Is he comfortable being pigeonholed as

a horror director?

"What I'm comfortable with is being allowed to work," he says with a

wide grin. "After House [Of America] and Resurrection Man I literally

couldn't get arrested. I'd committed some crimes against filmmaking, as

perceived by financiers; I had made films that were dark and didn't

make any money. The great thing about genre filmmaking is that for

someone like me who's not interested in social realism or social

comedy, it's probably one of the places I could exist and be employed,

because it requires imagination and intelligence and to play with ideas

in a cinematic way. Financiers don't look at you askance because you've

gone a bit weird on them. They want you to be weird. If that could be

my only resting place, I'd be happy with that. If that meant I could

make a film a year, I'd be very happy with that."

|

Equal parts Don't Look Now, Jacob's Ladder and

Patrick McGrath's Spider, Trauma revolves around Firth's grief-stricken

coma survivor who, attempting to get on with his life, moves into a

flat in a converted hospital and is soon befriended by a neighbour,

Charlotte (Mena Suvari from Americans Pie and Beauty), who is into

crystals and all things spiritual, and who tries to help Ben find some

peace. But as his tenuous grip on reality starts to loosen, we are left

wondering not only about Ben's mental wellbeing, but whether the

ethereal Charlotte may be another figment of his disturbed imagination.

Equal parts Don't Look Now, Jacob's Ladder and

Patrick McGrath's Spider, Trauma revolves around Firth's grief-stricken

coma survivor who, attempting to get on with his life, moves into a

flat in a converted hospital and is soon befriended by a neighbour,

Charlotte (Mena Suvari from Americans Pie and Beauty), who is into

crystals and all things spiritual, and who tries to help Ben find some

peace. But as his tenuous grip on reality starts to loosen, we are left

wondering not only about Ben's mental wellbeing, but whether the

ethereal Charlotte may be another figment of his disturbed imagination.

For

Firth, Trauma was an opportunity not only to work with Evans again

For

Firth, Trauma was an opportunity not only to work with Evans again