He is filming the sequel to Bridget Jones’s Diary nearby, which he finds ‘very weird... Because since the first one came out, we’ve been besieged by questions about when we were going to do the next one. That made it feel like a neglect of duty not to, but now we’re doing it there is a scepticism. People say, “Oh, are you sure that’s wise?” and, “Aren’t you just trying to cash in on the first one?” That encapsulates the dilemma of the sequel world.’ I wonder if he and his co-star Hugh Grant had to do weight training while Renée Zellweger fattened up again? He grimaces slightly and groans, ‘Well, I think a lot has been made of that’—but then his helpful side reasserts itself, and he says yes. Zellweger has larded up again, and no, he hasn’t done any training himself, but yes, he did for the first one because he thought he was going to have to get his shirt off, which would have embarrassed him. ‘Hugh was going to have to get his shirt off as well, so last time he was joking about us both eating salads. But this time he swears to me that he is not making the slightest bit of effort. Maybe he’s cheating and trying to throw me off my game—I don’t know,’ he says with a chuckle. Previous interviewers have ascribed much of Colin Firth’s character, and his decision to be an actor, to a miserable boyhood in England and overseas. His parents were lecturers born of Methodist missionary stock in India, and moved home between Nigeria (where Colin was born), Essex and St Louis, Missouri, before settling in Winchester. (There were three children by then, Colin being the eldest; his sister Kate is a voice coach, brother Jonathan an actor.) At his American school he was isolated because the other children were rough and he was a classic shorts-wearing English schoolboy. At his Winchester secondary modern he was slightly marginalised in the way new children from other countries often are, and to make matters worse, his parents didn’t let him or his brother or sister watch ITV. He disliked the teachers as well. According to the unhappy childhood theory, he learnt to act in order to deal with his peers, and he has played the outsider in later life—avoiding Hollywood, chat shows, fashion events, premieres and orthodontistry—because he was ostracised as a nipper. To be fair, his early public pronouncements did nothing to dispel the idea; at the start of his career it seemed that he only left his flat in Hackney, east London, to inform people he would never go to premieres, considered it vulgar to be rich, and hated it when actors he admired got Oscars because it prompted them to behave like fools. This theory is appealing because it fits with the aloof, alienated, intellectual roles he has played so well—oh, all right then, because it makes him sound like Darcy—but it is wrong. Actually, Colin Firth’s alienation is much more that of a lower-middle class liberal who was part of that generation of young, hard-leftist actors who entered British theatre in the 1970s and 1980s. Take if from a colleague: after acting opposite him in Another Country in 1983, Rupert Everett publicly derided Firth as a ‘living emblem of Redgraveism’ and a ‘red-brick communist’. ‘Oh God, yes,’ he says, when I bring up the premieres and Oscars thing. ‘I took up all sorts of positions, partly because of feeling guilty about having success when I was so young. It was a very Workers’ Revolutionary Party time in that respect. I was sharing a flat in Hackney with a guy who made sculptures and furniture but refused to sell anything because selling was whoring out. He would only give it away. All my friends were like that, and anyone who was making a living was seen as going along with the new yuppie ideal. Mind you, a lot of actors I know are a little bit uncomfortable with the premieres and the parties and the interviews. I think most actors are. I’m not unusual that way at all.’ By his own admission he would be very much at home in the north London novels of Nick Hornby, whom he befriended seven years ago while filming the adaptation of Hornby’s memoir Fever Pitch. Indeed, to dress for his role in Fever Pitch (the lead, based on Hornby himself) he wore many of his own can’t-be-bothered clothes, and he could easily have accessorised with other possessions and habits. He drives a generic German hatchback; like a pint and a curry, or good wine and Italian; hates reality television; accumulates books and CDs; would probably be lost for words if he met Bob Dylan. His politics, which are very much in keeping with his parents’, are keener and more active than the average disillusioned liberal’s, though. He campaigns for Fair Trade, Survival, Amnesty International and the rights of asylum seekers in Britain. People who knew him at school say he was sociable, fancied, a bit in the school plays. True, he hung around with the bohemian, long-haired blokes who like difficult 1970s rock music even after punk had hit Hampshire (the music’s pomposity suited him at he time, he says), but there was nothing seriously wrong. ‘No, I didn’t have an unhappy childhood. There were times when I was a bit dislocated, but it has given me as many benefits as disadvantages. There is a thin line between being a misfit and being the centre of attention, and there were brief periods when I felt a bit cock-of-the-walk. ‘I was sometimes slightly culturally removed, but I lived in other countries a lot. I suppose that has had an effect because as an adult I have tended to find partners who are not English [his first wife, the actress Meg Tilly, is Canadian; Jennifer Ehle, who he went out with after co-starring in Pride and Prejudice, was brought up in America; and his wife, Livia Giuggioli, with whom he has two young children, Luka, three, and Matteo, just under a year, is Italian], and I have spent a lot of time out of the country as an adult as well as a child. I am very attracted to people who are not English, and I am very interested in other cultures, and I love this country much more by virtue of the fact that I can see it from a distance. There are a lot of actors who are like that—part of what makes you want to do it is not feeling particularly locked into one identity. I think your ego has got to be a bit wobbly really.’ Firth decided he wanted to be an actor when, aged 14, he saw Paul Scofield in A Man For All Seasons, and ‘realised you could communicate great truths through acting’. He moved to London at 18, alone, just to be near the theatres; he worked as a telephone receptionist at the National Youth Theatre while applying for auditions at drama school, getting a place at the Drama Centre soon after arriving. His sister Kate once told a newspaper that their mother and father ‘didn’t think success as an actor was a real possibility’, which makes you wonder how young Colin’s decision went down with his academic parents. I ask him if he was closer to his mother or father, but this is the one question that he fails to take in his helpful stride. ‘It varied according to my age. But this is a conversation that would probably be better if my parents were present. It’s a tricky one to get into, so I’d rather they didn’t read it in The Telegraph. So, I would say that my family are all still there, they’ve stayed together all these years and so that speaks to you of it being quite functional, to an extent. But I think I should just leave, I really do.’ I am just curious because creative boys, especially eldest sons, often tend to be closer to their mothers in adolescence, and feel a bit displaced. And then there’s the ‘wobbly ego’.

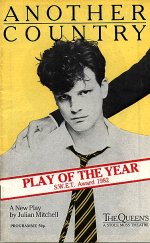

It seems to have ended happily anyway. When he left the Drama Centre, Firth walked straight into the stage version of Another Country, which was the hit play of the early 1980s, and his dad came and took photographs of the posters. Julian Mitchell’s play, based on Guy Burgess’s turning to communism at his public school in the 1930s, was adapted into film, and between them the two versions launched a cadre of young English actors including Firth, Everett, Daniel Day-Lewis and Kenneth Branagh. Firth was versatile enough to play both leads; on stage he played Bennett the traitor, on film Judd the Trotskyite. Like the rest of the Another Country set, Firth has worked constantly ever since, although there have been better times than others. He reached a peak of sorts when he played Robert Lawrence, a disabled Falklands veteran, in the BBC’s 1989 television play Tumbledown, which attracted controversy with its bleak depiction of Army life and warfare. Things went wrong in a notorious Hollywood fiasco when he took the lead in Valmont, Milos Forman’s version of Laclos’s 18th-century French novel Les Liaisons Dangereuses. Valmont came out around the same time as Stephen Frears’s adaptation of the stage play, and was entirely eclipsed. Firth, then 30, married his Valmont co-star Tilly, and they had a son, Will, now 12. They moved to thew wilderness of British Columbia for two years (her decision; he ‘rather fancied the quaint idea of the wilderness’, but it was ‘too lightweight’) and he stopped work for a year. It sounds grim. At one point he was writing to theatres in Vancouver with an account of his work to date, offering to do children’s workshops.

His new film is Girl With a Pearl Earring, the film of Tracy Chevalier’s novel, in which he plays the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer. The story is about the family’s maid, Griet, and Vermeer’s decision to paint a portrait of her, against the wishes of his wife. As Firth says, Vermeer has something ‘in common with the Darcy character in that he is seen through the eyes of someone else’. Does he like the film? ‘It is very hard to give in to completely liking anything you are in at first,’ he replies. ‘But I think there is a lot about it that is strong and takes my breath away. I think it is very brave in being serious as it is. It is unusual these days to find a script that doesn’t want to employ a bit of irony, because most people who tell stories and make films are very frightened of seeming naive.’ Vermeer is an older, more family-oriented role than we are used to seeing Firth play, and it demonstrates that he will be one of those actors who get better as they move through middle age: Bob Hoskins, Bill Nighy. He himself seems to suspect it, remarking only half in jest that he would like to become a rotund character actor and stop having to worry about his weight. Richard Curtis, who directed him in Love Actually, thinks the 43-year-old will become a Great British Actors because ‘of his magic ingredient: the dark, scary side that means he can play romantic figures who are unfriendly, scary and a bit damaged. He is so good at communicating what is hidden, and that’s important for a British drama, because so much of it is about hiding things—that’s why we do spy stories so well, as opposed to America, which is really the country of the Western. I think he will be gripping as a politician, or as a father with a problem family. Of course I have to say that in real life I find him the most sweet and charming of men. You have to dig very deep to find the dark side, although I suppose there must be some anger in there, or he couldn’t have done his cross performances.’ By this logic there must also be some romantic love buried in there too, or he couldn’t have done his soul-wringing declarations of love. Certainly you sense this when he talks about his wife, a producer 10 years his junior whom he met filming a BBC adaptation of Nostromo in 1995 in Colombia, and the time they spend at their home in Tuscany. He spend much of the summer holidays with his son Will in California—it’s the reason he can’t do long theatrical runs—and thinking about this, you realise that he is unusual for such a high-achieving making male, in that he has not only followed one wife to British Columbia and another to Tuscany, but also genuinely sacrifices bits of his career to be with his children. There is a work in Colin Firth’s oeuvre where love and anger seem to merge. It isn’t a film, but a short story called The Department of Nothing, which he wrote for a collection called Speaking with the Angel, edited by Nick Hornby and published by Penguin in 2000 to raise money for the TreeHouse school for autistic children. Hornby knew Firth wrote fiction which he usually ‘put in a drawer’, and asked him to do a story because he thought he’d be a good writer. The story concerns Henry, a boy on the edge of adolescence who recoils from the corruption and insensitivity of adults and finds solace in his grandmother’s fantastical stories. For the boy, real life—the Department of Nothing—is a place where imagination and pleasure are crushed, and where everyone conceals their true feelings but secretly wants to let them out. Firth says the boy in the story is not him although there are ‘elements’; but whatever the extent of the autobiography, there are many passages in which the author’s sympathy with the innocent, moral idealism of a child shines through, and illuminates a great deal about Colin Firth as a man and an actor. ‘Everyone wants to scream loudly and grab things without asking and break them, but that’s not allowed is it?’ says Henry at one point. ‘The trick is holding on to the magic to get you through.’

‘Girl With a Pearl Earring’ opens on Friday. |

‘Ye-es,

but it is probably a bit difficult. If this was well covered with my

parents,

I’d be happy to talk about it. It’s just that I don’t want them to read

stuff I haven’t said to them. But it is a very interesting observation,

and they are very different personalities, and I feel I’ve got some of

that, so that can create intimacy and it can also create clashes all

over

the place.’

‘Ye-es,

but it is probably a bit difficult. If this was well covered with my

parents,

I’d be happy to talk about it. It’s just that I don’t want them to read

stuff I haven’t said to them. But it is a very interesting observation,

and they are very different personalities, and I feel I’ve got some of

that, so that can create intimacy and it can also create clashes all

over

the place.’

At

least one writer who interviewed Firth at the time claims that he was

privately

cross that the other Another Country stars had risen faster and

higher than himself, although he has said he ‘doesn’t really remember’

how he felt about it. You can see why he might have been prone to worry

for a while after Valmont, though it seems harder to understand

now. Since he did his famous Darcy for the BBC’s Pride and Prejudice

in 1996 (having first declined the part because of the burden of

expectation

it would bring) Firth has commanded top-notch roles, and a respectfully

weak-kneed following unique among British actors outside the soaps.

At

least one writer who interviewed Firth at the time claims that he was

privately

cross that the other Another Country stars had risen faster and

higher than himself, although he has said he ‘doesn’t really remember’

how he felt about it. You can see why he might have been prone to worry

for a while after Valmont, though it seems harder to understand

now. Since he did his famous Darcy for the BBC’s Pride and Prejudice

in 1996 (having first declined the part because of the burden of

expectation

it would bring) Firth has commanded top-notch roles, and a respectfully

weak-kneed following unique among British actors outside the soaps.