The

Reluctant Hero

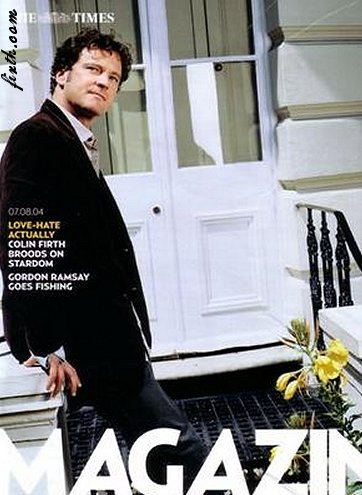

A decade on, the

nation’s bosom still heaves over his damp-shirted Mr

Darcy, but Janice Turner discovers Colin Firth never aimed to be a sex

symbol

|

|

The last time I

visited the Portobello Hotel was to interview gigolos as they were

photographed, oiled-up and naked, in a bath. I hesitate to mention this

to Colin Firth since our conversation in the hotel’s breakfast room has

hitherto had an earnest, thoughtful air. But he seizes on the subject:

“Were they good-looking? Did they take pride in their work? Were they

gay? Who were their clients?” They love a bit of filth, do actors, and

Firth breaks momentarily with his sensible interview persona to tell me

that Rupert Everett, a rent boy before drama school, had a client who,

many years later, became a close friend (although Everett has never

revealed to him they’d met before in seedier circumstances).

But then, are our romantic

leading men so far removed from gigolos? Both make a living knowing how

to arouse and satisfy female desire. The differences being that film

stars only pretend and are much better paid. Firth is in the highest

echelon of British male fantasy lovers: if Clive Owen is

bit-of-rough/soft, Sean Bean bit-of-rough/hard and Hugh Grant

posh/light, Firth is probably posh/dark. His appeal is not in what he

expresses but in what he is struggling to contain—Mr Darcy having to douse his ardour with

cold water or the artist Vermeer in Girl

with a Pearl Earring, channelling a longing for his

housemaid-model into fervent brushwork.

Firth serves a well-read

female clientele who abhor the obvious and crude, who could only fancy

a mainstream Hollywood hunk in an ironic way. He is subtle, complex and

refined enough for a number of unlikely ladies to emit earthy

“phwoars!” when I mention his name, and grill me jealously about what

he was like.

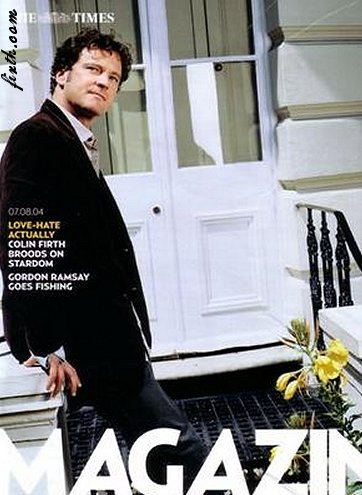

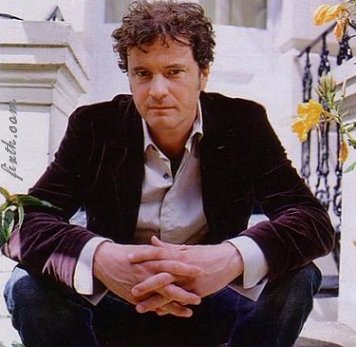

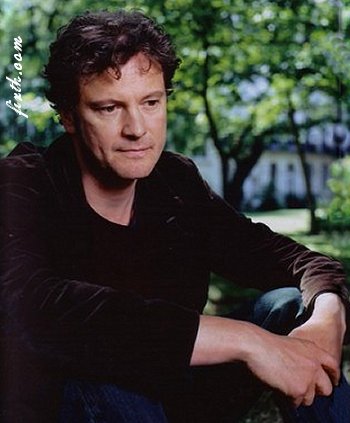

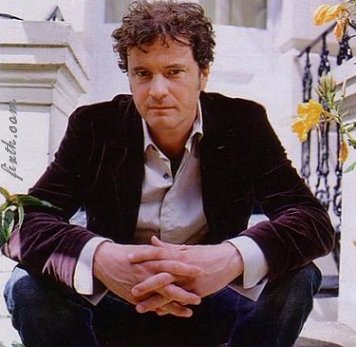

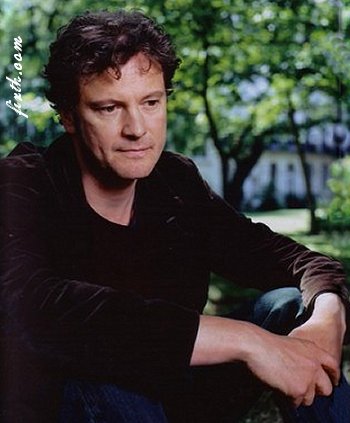

So, for

them: Colin Firth

this morning is wearing an unstructured midnight-blue velvet jacket

over jeans. He is as tall (6ft 1in) and as broad as a leading man

should be but seldom is. He is made of excellent stuff that is ageing

well: lush, wavy hair, good but not Los Angeles-white teeth, the

jawline of a leading man but the eyes of a watchful boy. The smile, a

surprise since it is rarely part of his on-screen armoury, renders him

younger. The sexiest thing about him, I find, is his voice: rich and

warm, with a nervous edge that in films plays as choked passion. So

later, when guests keep blundering into the breakfast room and he says,

“Come on, let’s find a room downstairs,” an involuntary exclamation

mark pops up in my brain. So, for

them: Colin Firth

this morning is wearing an unstructured midnight-blue velvet jacket

over jeans. He is as tall (6ft 1in) and as broad as a leading man

should be but seldom is. He is made of excellent stuff that is ageing

well: lush, wavy hair, good but not Los Angeles-white teeth, the

jawline of a leading man but the eyes of a watchful boy. The smile, a

surprise since it is rarely part of his on-screen armoury, renders him

younger. The sexiest thing about him, I find, is his voice: rich and

warm, with a nervous edge that in films plays as choked passion. So

later, when guests keep blundering into the breakfast room and he says,

“Come on, let’s find a room downstairs,” an involuntary exclamation

mark pops up in my brain.

He speaks in well-formed

sentences with a very precise vocabulary. He does more interviews than

most equivalent stars, and I suspect he likes to use them to

demonstrate his intelligence. Because, at his age, 43, he seems to

realise that being a romantic lead, which was far from his career goal,

is not enough. He is queasy about his sex symbol status, even queasy

about acting itself.

His latest film, Trauma, a low-budget British

chiller by Marc Evans, director of cult horror flick My Little Eye, is a return to

grittier, quirkier pre-Darcy roles. Firth plays Ben, an artist who

lives with his ant farm in a creepy converted hospital in Hackney, East

London. We meet him waking from a coma after the car crash that killed

his wife. But Ben is mentally unstable, an unreliable narrator, so

Firth, who is in every scene, does a lot of wild-eyed unshaven emoting

as Ben’s sanity unravels. A gruelling part, I suggest.

“Oh, we love all that,” Firth

says, sardonically (“we” being actors). “You can feel a bit of a

char-monkey sometimes just showing up, getting your make-up on and

phoning something in, then going home. In Trauma I was never off the set,

which means, after a while, you are part of the decision-making

process.”

Later, puzzling over the

phrase “char-monkey”, I do a search and the only thing that pops up is

an interview with Hugh Grant: “Imagine what it’s like, at 42, to be

sitting in hair and make-up,” says Grant. “It’s ridiculous. It’s all

right if you’ve written the film. But to be wheeled on, a char-monkey,

at the age of 42. I hate it.” Firth gives me an only slightly more

measured tirade: “It’s a fairly infantile day—you’re given a time to wake up, you’re

driven to work, someone puts on your clothes. You’re treated like an

18-month-old child!”

The romantic lead’s midlife

crisis appears to manifest itself as professional self-disgust. Being

adored for your handsome plumage starts to feel empty, and not a little

sad, after 40. You crave manly substance. But how to acquire it? Grant

tried producing movies with his company, Simian Films, but that has

stalled after two non-hits, Extreme

Measures and Mickey Blue Eyes.

Firth, however, has no ambitions to produce or direct, and despite

contributing a short story to a collection, Speaking with the Angel, edited by

Nick Hornby, he says he lacks the self-discipline to write.

“I’ve been deformed by the

rhythms that acting gives you, which make you fickle,” he says. “You

give yourself to a job for three months as if nothing else in the world

exists. And then you drop it like a stone. As a director, you have to

make that investment over a couple of years; I don’t know if I’ve got

it in me.

“The trouble is most of us

choose what we want to do when we are very young, and if it goes well

your success can tie you to it. I sometimes feel I’m stuck in a

profession only a 14-year-old would choose. Even though I love it.” “The trouble is most of us

choose what we want to do when we are very young, and if it goes well

your success can tie you to it. I sometimes feel I’m stuck in a

profession only a 14-year-old would choose. Even though I love it.”

Fourteen is the age at which

Firth, who plodded academically, devoted himself to acting. After

school he found backstage work at the Shaw and National Theatres before

drama school, and was then instantly scooped into the stage play Another Country with Rupert

Everett. The film version followed. Firth has never done the struggling

actor bit, toiled in rep or been out of work.

The Firth template was

moulded early on: the sensitive victim of an experience so terrible it

shuts down his emotions. In Tumbledown

and A Month in the Country

the damage was done in battle, in the Falklands and First World War

trenches respectively. It was this ability to convey simmering internal

conflict—as much as Firth’s dark looks—that made him a perfect Mr Darcy. Any

actor who could embody every teenage girl’s literary crush and that

most potent archetype of female desire, the distant, withholding but

powerful man unlocked by love, would stir half the nation’s loins. But

Firth says it was “the most improbable thing ever to happen to me as an

actor. People would have howled with laughter if I’d tried to predict

it. In fact, they did when it first happened.”

He quotes a theatre review of

a few years before: “Colin Firth doesn’t have enough romantic charisma

to light a 50-watt bulb.” And he was 33: “Too long in the tooth to play

the romantic stuff. I thought this would be my last throw of the dice.”

It’s a decade since Darcy, but women have not forgotten, and many fan

sites celebrate a wet-shirted Colin. Such as firthfrenzy.com or

firth.com, the latter a fastidious, stalkerish temple to their hero,

who is respectfully referred to as ODB (Our Dear Boy). They send him

edifying books as well as their panties: he is probably pursued by the

most intelligent horny women in the world.

“I have no idea what Tom

Cruise’s fans feel about him,” says Firth, uncomfortably. “There are

some actors who, wherever they go, people show up because they think

they are fantastic. Then there are slightly marginalised people who are

like somebody’s secret. I feel like a second division football team

that has this following who are more into it for the fellowship of each

other.”

I ask if he’s ever “googled”

himself for fun and he shudders. “That way lies madness. It would be

horrendous to listen to people who don’t know you discuss you in this

proprietorial way.”

Post-Darcy, most of his roles

have had a similar dramatic arc: romantically hurt guy healed by new

love, as in his last Hollywood vehicle, Hope Springs, a rom-com so silly

and limp it appears on lists of worst movies ever. He has a sideline in

cuckolds: uptight upper-class ones in The

English Patient and Shakespeare

in Love, or gloomy souls dumped for a more fun guy, as in Love Actually.

He is aware of his

repertoire’s limitations: “I got a bit of a jolt in Girl with a Pearl Earring when the

director said something about my brooding looks. And I thought, that

wasn’t supposed to be a f****** brooding look!” But the darkness is all

external. “I’m not a brooding person,” he insists. “But when it comes

to things like music or literature I am drawn to the dark stuff. That’s

what is most passionate, risky and interesting.” Trauma director Evans

describes Firth as “the most even-keeled, amusing, easy-to-be-with

person. I’ve never seen a dark side to him except on screen.”

Firth in

person does convey

an ease with himself, probably attributable to his solid family

background. His parents, now around 70, are both academics, whose

postings to America and Nigeria gave Firth, his younger brother and

sister a peripatetic childhood. This bookish environment explains his

fear of “char-monkey” vacuity and a tendency to intellectualise his

roles. He spent hours studying Vermeer for Girl with a Pearl Earring,

prompting Scarlett Johansson, who didn’t even read Tracy Chevalier’s

book, to comment drily: “Colin probably thinks he painted all the

paintings himself.”

It was also an ascetic and

thrifty upbringing. “It annoyed me sometimes that they weren’t more

avaricious. I would like to have had more gadgets in the house, more

expensive toys.” The kind of childhood that makes him feel, even today,

“conditioned to save silver foil because it used to be expensive”, is

an excellent inoculation against the meretricious world of movies.

Firth has never been enamoured of Hollywood, never chased it hard even

after Bridget Jones’s Diary,

his biggest box-office hit. “Los Angeles is such an untenable place to

be,” he says. “People come home and go straight to their answering

machines, obsess that they aren’t invited to some premiere. You laugh

it off for a week or two, then you get sucked in.”

But

neither is America always

enamoured with Firth, often reading his English restraint as woodenness

and preferring the more quicksilver charms of Hugh Grant. Although they

seldom meet, there is an undeniable rivalry between the two, played out

in their on-screen fist-fight in Bridget

Jones, with a rematch in Edge

of Reason, out later this year. Grant’s character—witty, sexy but heartless Daniel Cleaver—is the closest he has played to his real

self. And there is much of the slightly pompous decency of Mark Darcy

in Firth. But

neither is America always

enamoured with Firth, often reading his English restraint as woodenness

and preferring the more quicksilver charms of Hugh Grant. Although they

seldom meet, there is an undeniable rivalry between the two, played out

in their on-screen fist-fight in Bridget

Jones, with a rematch in Edge

of Reason, out later this year. Grant’s character—witty, sexy but heartless Daniel Cleaver—is the closest he has played to his real

self. And there is much of the slightly pompous decency of Mark Darcy

in Firth.

While Firth’s intensity means

he is often cast as an artist (Trauma,

Pearl Earring, Hope Springs) or writer (Love Actually) the spivvier,

shallower Grant plays someone who sells books (Notting Hill, Bridget Jones) or

paintings (Mickey Blue Eyes).

At this, Firth gives a small, satisfied smile.

“Hugh is a

brilliant

raconteur, a very funny guy,” he says. “In the DVD commentary for Love Actually he takes the piss out

of me relentlessly. He says, ‘In this scene they photographed him

higher up to try and make him look thinner.’ Or, ‘What’s that rinse

he’s using in his hair?’ It is very funny. The rights and clearances

department at Universal sent me the tape; they thought I might sue. But

if I don’t play the game it will seem rather petulant.”

But in the private

sphere it

is Grant who is cast in darkness while Firth basks in the sun. Grant

has looked anchorless since he split with Liz Hurley, bouncing around

the social pages, creating kiss-and-tells. Meanwhile, Firth seems

profoundly happy with his Italian wife, Livia Giuggioli, 33, a TV

producer he met on the set of Nostromo

in 1997. Nick Hornby has described Livia—with her beauty, culinary skills and PhD—as “joke-perfect”. Her attitude to the

cult of Darcy is amused bewilderment. They have two sons, Matteo, born

last year, and three-year-old Luca, whose cute bilingualisms Firth

proudly recounts. Italy, where he spends around three months a year,

also gives Firth respite from the low-level but wearing hassle of fame.

Firth is keen to point out he

has another son, Will, 13, by Meg Tilly, the Canadian actress he met

filming Valmont in 1989.

Firth moved to backwoods British Columbia for five years, at some price

to his career, until the relationship finally broke down. After that,

he spent stints as a single parent during Will’s long summer visits.

A solidness in his personal

dealings has, he says, been his ballast against the instability of his

profession. “My interpretation of growing up is mostly to do with a

capacity to stick with something. Whether it is a professional project,

a mission or a marriage.”

For the jaded fortysomething

romantic lead, a rich home life is a grand compensation. It certainly

stops any fears about losing your looks. I ask Firth if he worries

about body-revealing bedroom scenes as he gets older. “I go for a run,”

he shrugs. “I know that if I ate everything I wanted I’d turn into a

blob and that’s age. But I could never take the time it would require

to get my body up to Los Angeles standards. I would change profession

first.”

Trauma is released

on August 27

|

So, for

them: Colin Firth

this morning is wearing an unstructured midnight-blue velvet jacket

over jeans. He is as tall (6ft 1in) and as broad as a leading man

should be but seldom is. He is made of excellent stuff that is ageing

well: lush, wavy hair, good but not Los Angeles-white teeth, the

jawline of a leading man but the eyes of a watchful boy. The smile, a

surprise since it is rarely part of his on-screen armoury, renders him

younger. The sexiest thing about him, I find, is his voice: rich and

warm, with a nervous edge that in films plays as choked passion. So

later, when guests keep blundering into the breakfast room and he says,

“Come on, let’s find a room downstairs,” an involuntary exclamation

mark pops up in my brain.

So, for

them: Colin Firth

this morning is wearing an unstructured midnight-blue velvet jacket

over jeans. He is as tall (6ft 1in) and as broad as a leading man

should be but seldom is. He is made of excellent stuff that is ageing

well: lush, wavy hair, good but not Los Angeles-white teeth, the

jawline of a leading man but the eyes of a watchful boy. The smile, a

surprise since it is rarely part of his on-screen armoury, renders him

younger. The sexiest thing about him, I find, is his voice: rich and

warm, with a nervous edge that in films plays as choked passion. So

later, when guests keep blundering into the breakfast room and he says,

“Come on, let’s find a room downstairs,” an involuntary exclamation

mark pops up in my brain.

But

neither is America always

enamoured with Firth, often reading his English restraint as woodenness

and preferring the more quicksilver charms of Hugh Grant. Although they

seldom meet, there is an undeniable rivalry between the two, played out

in their on-screen fist-fight in

But

neither is America always

enamoured with Firth, often reading his English restraint as woodenness

and preferring the more quicksilver charms of Hugh Grant. Although they

seldom meet, there is an undeniable rivalry between the two, played out

in their on-screen fist-fight in