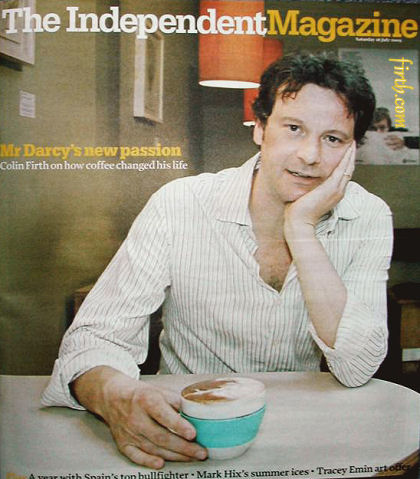

Colin Firth:

My toughest

role ever

Colin Firth is one of

Britain's most dashing actors. But now he faces a new challenge:

fighting for the world's poorest coffee farmers. He talks to Marina

Cantacuzino

|

|

How do you tell

consumers that their cappuccinos are driving someone somewhere deeper

into poverty? How do you kick down the doors of the big coffee roasters

until they're shamed into trading fairly? And how do you use celebrity

to make a noise without trivialising the issue? These are just some of

the dilemmas facing Colin Firth since he took on the role earlier this

year as a director of Progreso—a new coffee chain whose appearance on

our high streets may finally provoke Starbucks and its competitors to

recognise the humanitarian crisis that lies behind the coffee they sell.

The vision for Progreso is surprisingly subversive—a global chain that offers individuality

to the customer without pushing the brand, a business that pumps any

value added back into the hands of producers. Giving the coffee growers

of Honduras, Ethiopia and Indonesia a percentage of the business has

never been done before on our high streets. Nor has appointing as a

board member a respected big-name actor, albeit one still best known, a

decade on, for his sodden exit from a pond as Mr Darcy in the BBC

adaptation of Pride and Prejudice—a part that earnt him the epithet "the

male Ursula Andress". Firth's only credential is his burning desire for

change.

If there's one key thing he's learnt, he says, it's that the coffee

market fails the poor. It's a shameful story of complacent governments,

bullying multinationals and millions of coffee farmers around the world

facing economic ruin. Few of life's little luxuries can leave such a

bitter taste in your mouth—and there seems little prospect of

recent events at Gleneagles making much immediate difference.

Firth's position on the board, which until now has been deliberately

underplayed by star, chain and part-owners Oxfam alike, shows a level

of commitment rare among celebrities, whose endorsement is sought like

gold dust by charities; it's also an indication of just how seriously

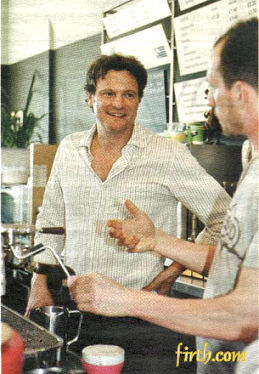

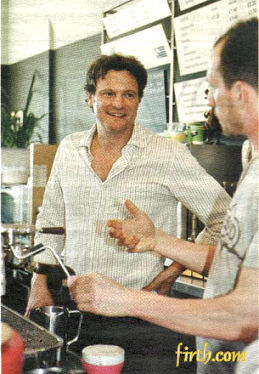

he takes his new role. This is not a gimmick: Firth has been to

Ethiopia to see Progreso's coffee producers at work, visited Glasgow

where the roasters Matthew Algie operate, and plans to roll up his

sleeves and get his hands dirty too. He has already had his health and

safety training and taken his turn behind the counter as a barista.

"Having Mr Darcy serve the coffee is a practical way of using my

profile without giving everyone earache," he says. Indeed, when he

turned up for work at Progreso's Portobello Road branch last month, it

seems that customers took it fairly in their stride. "People seemed to

think there was nothing more normal than having me serve their

cappuccinos and espressos," says Firth, and he promises to do it again.

He has been back from Ethiopia for a few

days when we arrange to meet at the café. It's here, on what he

calls "home turf", that he likes to hold his London meetings. Although

Ethiopia has evidently made a powerful impact on him, he's only too

aware that the world doesn't need to hear about yet another celebrity

in Africa, especially after Live8. "If you're going to sustain

commitment to any of this," he says, "there comes a point you can't

feed off the buzz. Even being horrified is a buzz. You've got to get

involved on an ordinary everyday basis." He has been back from Ethiopia for a few

days when we arrange to meet at the café. It's here, on what he

calls "home turf", that he likes to hold his London meetings. Although

Ethiopia has evidently made a powerful impact on him, he's only too

aware that the world doesn't need to hear about yet another celebrity

in Africa, especially after Live8. "If you're going to sustain

commitment to any of this," he says, "there comes a point you can't

feed off the buzz. Even being horrified is a buzz. You've got to get

involved on an ordinary everyday basis."

Progreso looks much like any other slick multinational coffee chain,

but here only fair-trade coffee is on sale. By cutting out the

middlemen, coffee farmers in the developing world get a fairer price,

while consumers know that, unlike at Starbucks, every cup guarantees a

fairer deal for the farmer. Wyndham James, Progreso's chairman and

formerly Oxfam's trading director, explains. "Our motto is sin

café no hai mañana," he says, "which has two meanings in

Spanish—'without coffee, mornings are no good',

and, 'without coffee, there is no future'. That is the story behind

coffee which Progreso wants consumers to understand and care about."

James

is struck by Firth's sincerity and commitment. "He wants to work in

something that makes a real difference," he says. But, quite apart from

being a dedicated board member, James knows that Firth is a powerful

draw to punters. On the day we meet, there is a gentle buzz around him

as he takes his place in the line for a coffee.

That

should come as no surprise. Firth has achieved a reputation—unwarranted, he always maintains—as one of the nation's most eligible

bits of posh, a dashing-but-stoical ladykiller, after starring in Fever Pitch, Bridget Jones's Diary,

parts 1 and 2, and Love Actually.

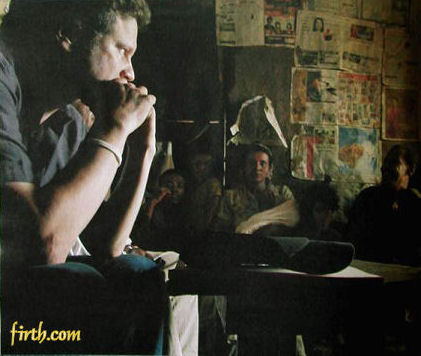

We start by talking about his trip with Oxfam to Ethiopia—a nation whose future is tied up in

coffee. Witnessing the gross power imbalance between the penniless

farmers and the profiting roasters was the start of what he calls "a

very sobering education". "I'd read all the reports, done my homework,

digested the facts," says Firth, "but actually meeting people whose

dream is simply to earn enough to buy a tin roof or send their kids to

school, makes it real. You're faced with emotional implications, the

sheer and simple unfairness of it all."

Ever since agreeing to support Oxfam's Make Trade Fair campaign two

years ago, Firth has immersed himself in the subject, invested a lump

sum to set up Progreso and even bought shares for the coffee producers.

Earlier this year in Geneva, he personally lobbied the World Trade

Organisation director general Supachai Panitchpakdi, about Oxfam's

campaign, and at a photo-call handed over their Big Noise global

petition with seven million signatures. The Big Noise aims to put

pressure on the big four roasters (Kraft, Sara Lee, Proctor &

Gamble and Nestlé), whose failure to embrace fair-trade

standards fans the flames of global poverty by creaming off profits and

allowing producers to go to the wall. Back home, Firth endeavours to

buy or drink only fair-trade coffee, and the message is getting through

to the rest of the population—certified fair-trade coffee is now the

fastest growing segment of the UK coffee market.

When Oxfam first approached Firth (at a time when the coffee prices had

plummeted to an all-time low) he was reticent to become yet another

celeb banging on about yet another cause: he knows it can backfire

badly on both charity and star. Before now his approach to activism was

radical but low-key. As a long-time supporter of Amnesty and Greenpeace

he's paid his subscriptions, written letters, and been on protest

marches. What changed?

"I was beginning to think I was banging my head against a brick wall

and, by the time Oxfam approached me, I was wondering if perhaps, since

I'm accorded a voice because of the celebrity factor, I should start to

use it," he says. "But it's a great responsibility. There are so many

more qualified voices than mine who don't have a chance of getting

heard. I detest the fact they have to use celebrities to do the jobs

for them but if that's what it takes then that's what I'll do."

On his second day in Ethiopia, Firth came face to face with how awesome

this responsibility is. While visiting the Choche co-operative in the

heart of the Kaffa region, the birthplace of coffee, he is welcomed

with a coffee ceremony (evidence that the golden bean is much more than

just a commodity here). "I was greeted with enormous grace and then

their boss who was high in the union leadership said something that

stayed with me for the rest of the trip. 'Three times we've been

visited by well-meaning people,' he said, 'and nothing has changed.' It

was very chastening and I came to see how close my visit was to being

bogus and ineffectual. I knew I had to have something to say for myself

or I'd just be another disaster tourist. There was no point in giving

empty reassurances, so I told him I couldn't promise anything in terms

of change, but that it might be in my power to get his voice heard. I

asked him what he wanted to tell the consumer."

What Firth heard from the leader of the Coche Co-op, and then again and

again from all the coffee farmers he met, was not an account of extreme

hardship—although there was plenty of evidence of

that—but a plea for a fair price for the

region's top-quality arabica coffee. "The people are so emotionally

bound up with the coffee. Their pleading was not on the basis of

poverty but of quality. 'Give us a fair price, and we'll grow coffee on

every last square centimetre of land,' they were saying."

You sense Firth's uneasiness at having discovered such beauty amid such

deprivation. "We arrived in Addis Ababa and everything felt so raw and

new," he says. "This feeling just grew with all of us as we fell in

love with the place. It's so troubled as a country but the people we

met were friendly and eloquent, which made me feel even more useless.

No one projected misery or despondency—far less than on Oxford Street,

actually. I met the owner of a little wooden hut with 'Art Gallery'

written in crude paint strokes. He showed us his plans to build a

million-pound hotel looking down over Addis. It struck me as a

remarkable that a man who was lucky to have enough to get him to the

end of day still had this kind of dream."

Since

Firth's return from Ethiopia, the one thing that keeps nagging at him

is that we are all compliant because we are all consumers. "The farmer

at the end of the chain isn't asking for charity, he's just asking for

a fair price," he explains. "Whenever we told Ethiopians that the price

of a cup of coffee on the high-street is as much as £2.75, there

was this incredulous laughter and then they shook their heads with

worldly resignation. It takes 24 beans to make a cup of coffee and yet

in a bad year the producer is selling a kilo of beans for just 5p. So

who is making the profit? Not the farmer." Since

Firth's return from Ethiopia, the one thing that keeps nagging at him

is that we are all compliant because we are all consumers. "The farmer

at the end of the chain isn't asking for charity, he's just asking for

a fair price," he explains. "Whenever we told Ethiopians that the price

of a cup of coffee on the high-street is as much as £2.75, there

was this incredulous laughter and then they shook their heads with

worldly resignation. It takes 24 beans to make a cup of coffee and yet

in a bad year the producer is selling a kilo of beans for just 5p. So

who is making the profit? Not the farmer."

The problem is that, in the developing world, those who depend on

farming to survive are suffering because trade rules are rigged against

them. The solution is simple, according to Wyndham James. "The major

roasters need to commit to help solve the crisis by stopping exploiting

their position in the supply chain," he says. "They should guarantee a

decent price to producers, they should buy more fair-trade coffee and

should improve the quality of all the coffee they buy."

It sounds simple but James, like Firth, Oxfam and the farmers

themselves, knows there is little chance of the roasters doing this

unless pressure is put on them by governments. For this reason, Firth

is now determined to use his fame to give a voice to those who don't

have one. He's also determined that in three years there will be not

two, but 20 Progreso outlets in the UK.

Sitting on the Progreso board is clearly one of his main priorities

these days, even if regular attendance can't be guaranteed around his

filming schedule. "I can't apportion time evenly, not even to my

children," he says, "but if I'm away for six months the board meets

without me, the coffee shops continue to trade, and from wherever I am

I can continue to spread the word."

After spending several hours with Firth, talking intensely about

Progreso, Oxfam and the coffee crisis, he is clearly in this for the

long haul: his reticence is a reflection of his integrity, his passion,

a conviction that Progreso and the issue on which it was founded has to

be taken seriously.

If you want to help make trade fair, sign The Big Noise petition at

www.maketradefair.com

|

Since

Firth's return from Ethiopia, the one thing that keeps nagging at him

is that we are all compliant because we are all consumers. "The farmer

at the end of the chain isn't asking for charity, he's just asking for

a fair price," he explains. "Whenever we told Ethiopians that the price

of a cup of coffee on the high-street is as much as £2.75, there

was this incredulous laughter and then they shook their heads with

worldly resignation. It takes 24 beans to make a cup of coffee and yet

in a bad year the producer is selling a kilo of beans for just 5p. So

who is making the profit? Not the farmer."

Since

Firth's return from Ethiopia, the one thing that keeps nagging at him

is that we are all compliant because we are all consumers. "The farmer

at the end of the chain isn't asking for charity, he's just asking for

a fair price," he explains. "Whenever we told Ethiopians that the price

of a cup of coffee on the high-street is as much as £2.75, there

was this incredulous laughter and then they shook their heads with

worldly resignation. It takes 24 beans to make a cup of coffee and yet

in a bad year the producer is selling a kilo of beans for just 5p. So

who is making the profit? Not the farmer."