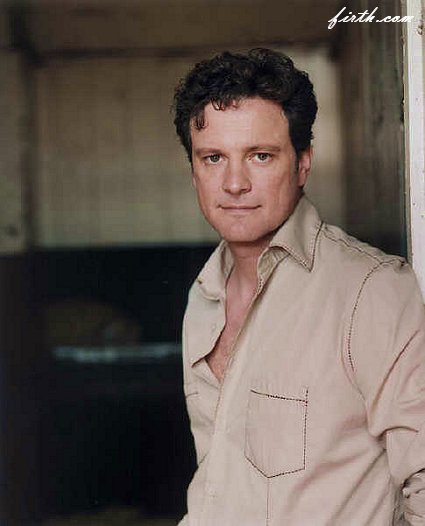

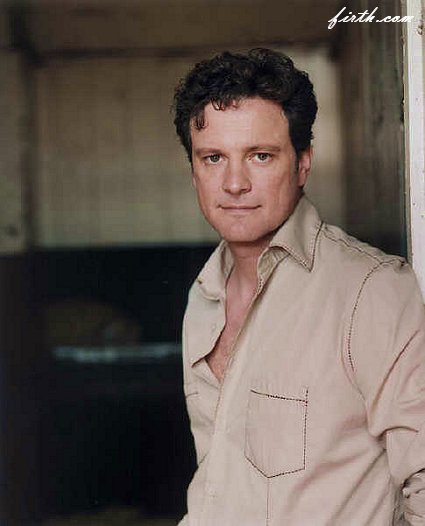

Books That

Made a

Difference to

Colin Firth

The eternally watchable costar of Bridget

Jones: The Edge of Reason goes for

psychological intrigue, moral mud

puddles, and lyrical truth-telling.

|

|

When I’m really

into a novel, I’m seeing the world differently during that time—not

just for the hour or so in the day when I get to read. I’m actually

walking around in a bit of a haze, spellbound by the book and looking

at everything through a different prism.

I’m paraphrasing terribly from a theory I came across years ago, but

there was this idea that everyone leads a kind of secret life. All of

these things are going on around us that we don’t process consciously

but that stay with us. There’s a school of thought that inanimate

objects can make you feel certain things and you don’t know why. You

pick up a green mug and you drink coffee out of it and you’re not

thinking about anything except whether the coffee is good or bad. About

an hour later, you feel depressed and you don’t know why. Perhaps the

mug is exactly the same color as your grandmother’s. You’re aware of

the emotions but you didn’t know your subconscious went through a whole

thing—remembered something, relived something, and fed it back to you.

So a book can pull out responses that would be dormant otherwise. I

find that a very valuable thing to have as a possibility. I’m not

simply responding to the author’s vision. The joy I take from a book is

mine. It comes from me.

Colin Firth next appears in Nanny

McPhee, which opens in March.

|

|

The Notebooks of

Malte Laurids Brigge by Rainer Marie Rilke

This is not really a

novel at all; it’s sort of a montage based roughly on the experiences

of the author as a young man. Certain individual passages are

riveting—like his description of Beethoven: “A man whose hearing a god

had closed up, so that there might be no sounds but his own.” What a

fascinating way to look at the contradiction of a musician who is deaf

but hears extraordinary things in his head. Rilke also writes of an

illness during which certain absurd fears strike him—that a piece if

thread might be as sharp as a steel needle, or that he might start

screaming. I don’t think I’ve ever read such descriptions of what it

would be like to lose your grip. He has a vision that makes you less

sure of your surroundings—and I find that stimulating.

amazon.com

or amazon.co.uk

|

|

|

|

The Power and the

Glory by Graham Greene

This is about a man—the

whiskey priest—on the run in a Mexican state during a purge of

religious figures. The most poignant thing in the story, for me, is

that the priest has had a child. He wants to repent, but how can you

find salvation when you can’t hate the sin? He’s stuck in that

paradox:The one thing that prevents him from repenting is love. That so

interests me—the idea of looking for spiritual salvation in what is

otherwise an impossibly compromised life.

amazon.com or amazon.co.uk

|

|

|

|

The Leopard by Guiseppe de Lampedusa

I wouldn’t give a damn

about the world of this book were it not for the fact that Lampadusa

draws you into it in such an intoxicating fashion. The descriptions of

19th-century Sicily were written with such melancholy, honesty, and

lack of sentimentality that I found myself thinking this era was the

most important thing. What blew me away, though, were the passages

about death. Extraordinary.

The

prince, whose family is part of the dying aristocracy, says sleep is

what the Sicilians want. They don't want anything forward looking. All

their magnificent history and the things they worship—their cathedrals and castles and

heritage—are things Sicilians love only because they’re dead. It’s a

romance with sleep and death—a desire for what he calls voluptuous

immobility.

amazon.com

or amazon.co.uk

|

|

|

|

Preston Falls by David Gates

Doug Willis is a man

who’s holed up in his country place after his wife and kids go back to

town. His marriage is in a bad state, and he’s obviously in some of

kind

of midlife crisis. I’m so intrigued by how Gates describes the fantasy

world of men, and how many of them want to be the kind of guy who can

talk about engines, who knows Keith Richards guitar chords—as if that’s

going to matter in your 40s. I can see why women might only be able to

read this as a science experiment, a sort of “Look what happens to men

when you pull their wings off!” But there’s a very tender note struck

in the last scene. The couple has decided to split up, and Willis walks

out late at night. Gates has taken you to a point where you think their

relationship is irredeemable, but he shows there’s that thing you can’t

put in the equation: The wife still goes after him. I found that quite

moving—that in the end love feels like that, like familiarity.

amazon.com

or amazon.co.uk

|

|

|

|

Saint Maybe by Anne Tyler

How do you evaluate a

deed that has brought catastrophe? Tyler writes about Ian Bedloe, who

thinks he’s doing his brother a favor by telling him that his wife is

unfaithful, and the brother subsequently drives a car into a wall and

dies. Ian is 17 and said something stupid and, as it turns out,

incorrect. I’m not a great believer in sitting cross-legged on a

mountaintop throughout your life as a spiritual quest. What I find

interesting is how an enormous spiritual journey unfolds in the

banality of life. When Ian asks a minister how he can redeem himself,

the minister replies, “You can raise the kids.” It means throwing away

college, throwing away his girlfriend, throwing away everything in

order to be a father to these kids. At no point is it ever considered a

noble thing, but he takes it on. He lives for something other than

himself.

amazon.com

or amazon.co.uk

|

|

|

|

Light in August by William Faulkner

It’s not the sheer art

of Faulkner’s literary experimentation that I admire. I’m haunted by

the heat he describes, by the smells, which are almost always

revolting. I know that’s a strange reason to be attracted to an

author, but I love it when writing is as potent as it is here. This

novel is about sexual revulsion, racial revulsion,

self-revulsion. It’s such uncomfortable reading for modern

audiences. The problem with racial identity is overwhelming to the main

character, Joe Christmas. As a child, he heard nothing but whispering

about his mixed blood, and he learns to despise that part of

himself. This is a world where every piece of decency is

marginalized and suffocated. It’s funny, you know: This is my favorite

of these books and the one I find the most difficult to talk about.

amazon.com

or amazon.co.uk

|

|

|

|

The Corrections

by Jonathan Franzen

Franzen captures how

trivializing a family battle can be and how it can seem to be a fight

for survival when, in fact, you’re simply scoring points. Chip

represents so much of what I’m familiar with: highly intelligent,

educated people who become fractured and cast adrift. You can

liberate yourself from the rules, decide you don’t want to be on the

treadmill, you’re not going to be Joe Schmo—but once you’ve cut loose

from all that, you can be quite lost. Franzen shows how often love

between these people is impossible; how hard love is, how it isn’t

cozy; how problems aren’t something you can break down by everybody

hugging one another and forgiving and making it okay. It just blows up

in all their faces.

amazon.com

or amazon.co.uk

|

|