Don't photograph me from the

waist down

The film hunk Colin

Firth on set in Slovakia—what could be finer? Then we saw his trousers

|

|

Welcome to

Slovakia. We've come to photograph Colin Firth and to talk to him about

his latest film, Where the Truth Lies. There's me, the writer, and

Martin Kollar, a Slovakian photographer with Tiggerish bounce and a

quirky sense of humour, who surprises me by admitting that, until this

week, he'd never heard of Colin Firth. By way of background research,

Martin telephoned an ex-girlfriend working in London. She told him that

Firth is known as a bit of a heart-throb. That was probably all Martin

needed to know, but I added that Firth is believed to be a good

bloke—not a precious movie star—and a fine and versatile actor. I may

have said something about him being increasingly vocal as a campaigner,

though I don't recall using the word "soapbox".

We're

in Slovakia because Firth has come here to shoot yet another

movie. Filming started early in the morning and it's not likely to

finish until late at night. When Firth does finally become available,

we'll only have a few moments to take his photo, so to be sure we get

it right, we practise. We create a plausibly English environment, with

lime trees and horse chestnuts. Martin asks me to be Firth, stands me

on a soapbox, and holds a variety of framing devices behind me. The

most effective is an opaque filter, borrowed from the film crew. The

effect is stunning: sunlight brightens the filter so that I seem to

shimmer. We agree that Firth will look fantastic. Hours pass, and the

winter sun moves rapidly across the sky. Again and again, Martin

adjusts the lighting setup as we are promised Firth will be with us

soon. Every so often we wander over to watch the shooting, only to find

Firth is central to every scene and can't be spared. Martin becomes

less Tiggerish by the minute. Me, I bite my lip.

Only at the last moment, just before the

sun drops behind a hill, does

it seem that we shall have Firth for a few minutes after all. But

there's a problem: his costume. We've come to talk about a film set in

the late 20th century, and Firth is dressed like a Roman soldier. He

dashes to his trailer to fetch something to wear over the top—but by

the time he returns, a grim-faced assistant director carrying a

clipboard and a walkie-talkie is waiting to call him back on set. The

pictures will have to wait. The photographer, now playing Eeyore,

resigns himself to losing the sunlight. Only at the last moment, just before the

sun drops behind a hill, does

it seem that we shall have Firth for a few minutes after all. But

there's a problem: his costume. We've come to talk about a film set in

the late 20th century, and Firth is dressed like a Roman soldier. He

dashes to his trailer to fetch something to wear over the top—but by

the time he returns, a grim-faced assistant director carrying a

clipboard and a walkie-talkie is waiting to call him back on set. The

pictures will have to wait. The photographer, now playing Eeyore,

resigns himself to losing the sunlight.

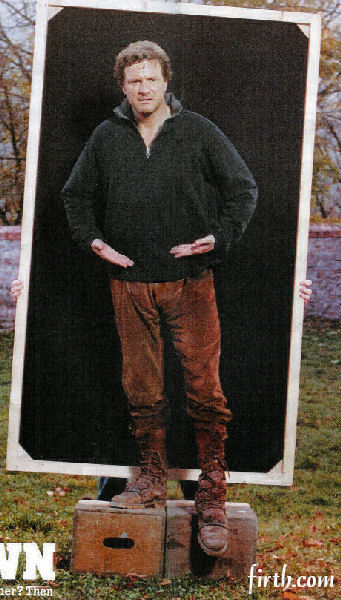

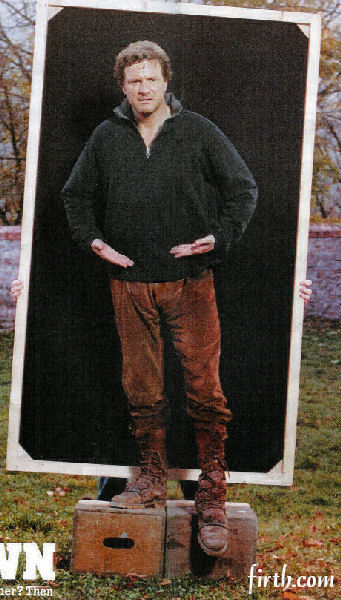

Then, just as Martin has finished dismantling his lights, Firth

reappears, accompanied by the assistant director and a publicist whose

exchanges with Martin have become increasingly embattled. We've got

five minutes, they say grimly. Martin springs into action, moving the

lights back where they were. Firth, wearing a sweatshirt over his

leather shirt, climbs into position. But just as Martin starts to take

some pictures, the publicist says we can only photograph Firth from the

waist up. Otherwise, Sunday Times readers would see his Roman trousers

and Timberland boots, also customised to look Roman. And we can't have

that.

It's at this point that the artist loses his cool. He throws up his

hands and says: "I can't do this. I can't make a hundred compromises in

one day!" The artist in question is Martin.

Firth steps down off the crate. "I'm sorry about your compromises." He

looks sincere, but it is impossible to rule out the possibility that

he's also a little amused. Martin is already regretting his outburst.

It's not Firth's fault, he says, and apologises effusively. Firth steps

back up and Martin places me behind him, holding a screen of black

felt. Look closely at the picture and you can see my fingertips.

It's not that Firth asks much, he says jovially. He doesn't demand

outfits by Armani, for instance, or Hugo Boss. He's willing to be

photographed with his hair and face smeared in glycerine — lending him

a sweaty appearance appropriate to a legionnaire but less so to a movie

star. He'd just prefer not to be pictured in trousers with a leather

gusset, if that's possible. "You try to be a good bloke," he says, "and

to make yourself available. But I don't want to open a magazine and

think, 'Why on earth did I let them do that?'"

Many

people might

think it more embarrassing to be filmed in some of the off-colour high

jinks of Where the Truth Lies: the sex, the drugs, the violence. Firth

is unlikely to send still photographs from this to his aged aunts.

Where the Truth Lies explores the dark and destructive side of showbiz

success. Vince Collins (Firth) and Lanny Morris (Kevin Bacon) are the

hottest showbiz partnership in 1950s America. When a beautiful young

woman is found dead in their suite, their world falls apart. Fifteen

years later, a journalist persuades a publisher to offer Collins $1m to

collaborate with her on writing the untold story. Through a variety of

conflicting accounts, the mystery is grippingly sustained until the

movie's end. The sex scenes, featuring Bacon and Firth together in the

same room as assorted young women, were anything but sexy, Firth

reports. "We ran through the morning with our curlers in. Then we ran

through it partially clothed, sorting out where the guy with the boom

microphone was going to be. Hopefully, not anywhere near me: it takes

all the sex out of it." Many

people might

think it more embarrassing to be filmed in some of the off-colour high

jinks of Where the Truth Lies: the sex, the drugs, the violence. Firth

is unlikely to send still photographs from this to his aged aunts.

Where the Truth Lies explores the dark and destructive side of showbiz

success. Vince Collins (Firth) and Lanny Morris (Kevin Bacon) are the

hottest showbiz partnership in 1950s America. When a beautiful young

woman is found dead in their suite, their world falls apart. Fifteen

years later, a journalist persuades a publisher to offer Collins $1m to

collaborate with her on writing the untold story. Through a variety of

conflicting accounts, the mystery is grippingly sustained until the

movie's end. The sex scenes, featuring Bacon and Firth together in the

same room as assorted young women, were anything but sexy, Firth

reports. "We ran through the morning with our curlers in. Then we ran

through it partially clothed, sorting out where the guy with the boom

microphone was going to be. Hopefully, not anywhere near me: it takes

all the sex out of it."

The film is based on a novel, in which Firth's character is American.

The director, Atom Egoyan, changed that: he fancied that a Brit could

be interestingly uptight alongside the unruly American played by Bacon.

The models he had in mind for Firth included David Niven and Rex

Harrison. As for the double act, Egoyan wanted Firth and Bacon to work

up their own routine, and helped out by creating plausible environments

for them: a club, a telethon studio. He even hired a professional

laugher to react to their jokes.

"People have said that the act is crap," says Firth, referring to

American reviews. "But if you go through the footage of the Rat Pack

and people like that, a lot of their stuff was crap by today's

standards. It was macho, often racist. I don't think our routine was

crap—anyway, it wasn't about having the best gags. We were more

concerned with creating glimpses of that world. It looks tired, like a

proper routine."

The actors sometimes had to play both 1950s and 1970s scenes in a

single day. "It was very, very bizarre. You're ageing 15 years, and

then going back to when you are young and everything was going well for

you—and then back again. But that is what actors do. I'm not

complaining: I find it exhilarating. You get ready and they say, 'We're

not doing that scene. The light's not right.' So you get ready for

something else, then they change their minds again.

"People have this idea that if you don't get it right you can do it

again. But you can't. Not unless you get 20 takes with Kubrick. Even

then, it can get worse, not better. You don't want to piss everyone off

because they all got it right—the other actors, the director, the

lighting people, sound. And if you do ask to have another try, they

might say, 'Sorry, but the scene coming up is even more important.' And

you are thinking, 'Oh, so this is for ever?' That's something you catch

yourself thinking all the time. I read a comment on the art of

translation: you have never finished, you just abandon it. With film,

that happens many times a day."

In person, Firth

proves much as I had expected. Tall and good-looking, sure. A teeny bit

earnest. And thoroughly polite: he goes out of his way to make himself

available, sitting down with me three times to make sure I have covered

everything. The first time, we speak for precisely 13 minutes. (The

publicist times it, presumably so I can't complain later that I've not

had long enough.) We sit on a bench in the freezing cold while the crew

rearranges the set. Firth looks preoccupied, and answers questions

defensively. ("I don't know how I choose the parts I play.")

The second conversation falls at the end of that day. Firth changes

into his own clothes, then wanders back uphill to find me, rather

than—as I'm sure he'd prefer—driving back to his hotel or to a

particularly good sushi restaurant he's discovered in Bratislava. This

time, he's more expansive. The publicist leaves us alone and we talk

for more than an hour. I even get him to open up on the mechanics of

acting, which I find fascinating, but which many actors prefer not to

discuss lest they sound pretentious.

Firth was born in Hampshire, moved to Nigeria where his father was

teaching, and returned to England aged five. He went to a comprehensive

school in Winchester. As a boy he dreamt of being a writer. "But when I

was 14 it came to me that I could act." So he spent two years at the

Drama Centre in London, and landed his first role on the professional

stage as the lead in the award-winning 1981 production of Another

Country. After that, he joined the Royal Shakespeare Company. Firth's

film career began in 1984 in Another Country, with Rupert Everett. In

1989 he took the lead in Milos Forman's film Valmont. His lead role in

the TV drama Tumbledown, based on the Falklands war, earned him the

Royal Television Society best-actor award and a Bafta nomination. He's

since starred in the films The English Patient, Fever Pitch,

Shakespeare in Love, Bridget Jones's Diary, Love Actually, and Bridget

Jones: The Edge of Reason. In 2002 he was reunited with Everett in a

film of Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest.

But the part he's best known for remains Mr Darcy. More than 10m

viewers tuned in to the BBC's 1995 TV adaptation. Worldwide, more than

100m have seen it. On Google, if you search for Colin Firth and Pride

and Prejudice, you'll find about a quarter of a million websites. Most

feature gushing commentary from women viewers, such as: "Oh, Mr. Darcy!

How often in my reveries have I longed to console you." Or describing

their all-time-favourite screen moment: "When Mr Darcy emerges from the

lake (mmm Colin Firth!!!)".

The screenwriter Andrew Davies, who adapted the novel for the BBC,

makes a point that's often overlooked: that Darcy represents a

considerable acting challenge. "At the start, the actor mustn't give

away too much the fact that Darcy is going to be a sympathetic

character," he says. "But he must play him in a way that he's not just

a really nasty person who turns into a really nice person." Firth's

solution was to stay very still and to convey everything through

Darcy's eyes. "I thought to myself, 'This is where he wants to go

across the room and punch someone. This is where he wants to kiss her.

This is where he wants sex with her right now.' I'd imagine a man doing

it all, then not doing any of it. That's all I did."

Kevin McKidd, the star of the BBC's epic drama Rome, has been playing

opposite Firth in Slovakia. Firth is "expected to smoulder all the

time", says McKidd. "And his face, in repose, is a bit like that. But

Colin injects fun into the work, and this business should be fun. He

has the right balance between paying the job the respect it deserves

and not taking himself too seriously." In this respect, perhaps having

children helps. In 1989, Firth entered into a relationship with Meg

Tilly, his co-star in Valmont. Their son, Will, was born a year later.

In 1997 he married an Italian, Livia Guiggioli, whom he met while

filming Nostromo. They have two sons: Luca, aged four, and two-year-old

Matteo. "Your own children, by their very existence, make you rethink

everything. They keep your mind alive and question you, and mock you."

Since meeting Livia, he's learnt to speak her language fluently—he once

described that as the most romantic thing he ever did. He's also become

heavily involved in cultural events at the Italian Institute in London.

For his efforts, he was honoured in May as a Commander of the Order of

the Star of Italian Solidarity. He'd see more of his family—and of the

Italian Institute—if he wasn't so often abroad on location. Why not

stay in England, I ask, perhaps do a spot more theatre?

"Theatre acting is infinitely easier

than film, in every way. You don't

have a scrambled process, you can't be messed around by the editor, you

have proper rehearsals and you're on stage before an audience. But

there are a million

reasons, noble and otherwise, for doing film. The

recognition is very high, for a start. And at its best, film is a

beautiful medium. It is wonderful that you can keep it. To me, Spencer

Tracy does not look dated. Nor does Garbo, even in her silent work.

Film doesn't disappear into the air. I find it devastating that you

lose theatre performance." "Theatre acting is infinitely easier

than film, in every way. You don't

have a scrambled process, you can't be messed around by the editor, you

have proper rehearsals and you're on stage before an audience. But

there are a million

reasons, noble and otherwise, for doing film. The

recognition is very high, for a start. And at its best, film is a

beautiful medium. It is wonderful that you can keep it. To me, Spencer

Tracy does not look dated. Nor does Garbo, even in her silent work.

Film doesn't disappear into the air. I find it devastating that you

lose theatre performance."

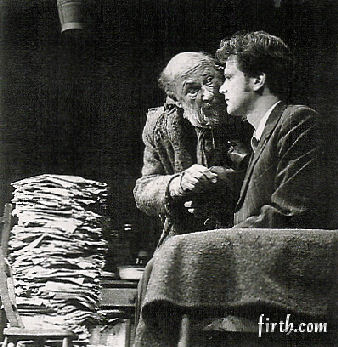

Firth's

not done much on stage since leaving the RSC, but he did win

excellent reviews in a 1991 revival of Harold Pinter's The Caretaker,

directed by Pinter himself. The experience evidently stuck with him.

"When something is that well written, and the production functions that

well, it gets under your skin." What was Pinter like? "Harold was

extremely practical and economic. His notes were not designed to reveal

what lay behind the text: they were to do with blocking. He might have

said, 'Why don't you sit down before you say that?' And I couldn't

believe how much that tended to solve the problems I was having. He

also treated the text as though it were someone else's. He would make

jokes about telling the author what he thought of it."

Firth was delighted when it was announced in October that Pinter had

won the Nobel prize: "He's a stunning writer and very important." Is he

equally impressed by Pinter's political views? Many people wish he

would stick to play-writing, not attacking George Bush, Tony Blair and

the war in Iraq. Firth curls his lip, assuming a scornful expression

hardly less familiar than the trademark smoulder. "Why should he not

have the views that he has? I don't understand this thing about

celebrities 'telling people what to think'. It's an English whinge. If

you don't like it, don't listen. I think Harold is courageous and

passionate."

Firth had long been

a supporter of Amnesty and Greenpeace, paying subscriptions, writing

letters, attending protest marches. But recently he became more

outspoken. "I didn't want the fact that I was famous to stop me, and

maybe it was irresponsible not to use it." In April he met Supachai

Panitchpakdi, the director-general of the World Trade Organization, to

discuss an Oxfam report on rich countries forcing poor ones to open

their markets, and dumping surplus crops. "I had the choice between

being the guy who smiles for the camera and says a few words, or doing

some homework and trying to make the issue my own," he says. "It's

hard, when you open up that kind of door, to close it again and do

nothing. You are open to attack. The cynics and those who don't give a

shit are constantly on the lookout for hypocrisy in everything that

might be well intentioned. Working with Oxfam, for example, and being

tremendously well off could seem like a contradiction. It's a fair cop.

But this is not all about giving away your possessions. We are all at

risk of being called hypocrites."

He adds: "I have a huge distrust of certainty and conviction,

particularly the crude type politicians like Tony Blair and Margaret

Thatcher have, that people seem to admire so much. Where do they find

that certainty? I don't believe it's possible to have that if you are

an imaginative person."

Our third conversation takes place in a pair of folding canvas chairs

in front of the director's monitors. Firth has put himself out for me

and covered a great deal of ground. Among other things, I ask if he's

ambitious ("I think I must be"), then about his long-standing interest

in writing fiction and, more recently, directing. We also discuss

travel and his attempts to play the guitar.

But as I sit at my computer in England, none of that seems half as

absorbing as the photo session in Slovakia. The whole thing was over in

just five minutes, but it seems to exemplify much that Firth told me

about the process of making a movie: the exhilaration, the uncertainty,

the dependence on good light. It even bears comparison, I like to

think, with Where the Truth Lies. It didn't specifically address the

destructive side of showbiz, nor was there a great deal of sex, drugs

and violence. But there was a rather tired partnership, comprising

Martin (the unruly one) and me (the uptight Brit). And there was ample

scope for conflicting accounts of what occurred, like the ones used by

Egoyan. Did Martin really throw a wobbly? Was the publicist a pain in

the bum, or just doing her best in difficult circumstances? Was the

real villain the assistant director with the clipboard and the

walkie-talkie?

Just one thing's for sure. There was a ghastly crime, with an innocent

victim. Not a naked woman dead in the bath, but a 45-year-old actor, a

good bloke, Commander of the Order of blah-blah, captured on film in

The Wrong Trousers, on a soapbox for all the world to see his horrid

leather gusset. As they say, Mmm, Colin Firth! ! !

|

Many

people might

think it more embarrassing to be filmed in some of the off-colour high

jinks of Where the Truth Lies: the sex, the drugs, the violence. Firth

is unlikely to send still photographs from this to his aged aunts.

Where the Truth Lies explores the dark and destructive side of showbiz

success. Vince Collins (Firth) and Lanny Morris (Kevin Bacon) are the

hottest showbiz partnership in 1950s America. When a beautiful young

woman is found dead in their suite, their world falls apart. Fifteen

years later, a journalist persuades a publisher to offer Collins $1m to

collaborate with her on writing the untold story. Through a variety of

conflicting accounts, the mystery is grippingly sustained until the

movie's end. The sex scenes, featuring Bacon and Firth together in the

same room as assorted young women, were anything but sexy, Firth

reports. "We ran through the morning with our curlers in. Then we ran

through it partially clothed, sorting out where the guy with the boom

microphone was going to be. Hopefully, not anywhere near me: it takes

all the sex out of it."

Many

people might

think it more embarrassing to be filmed in some of the off-colour high

jinks of Where the Truth Lies: the sex, the drugs, the violence. Firth

is unlikely to send still photographs from this to his aged aunts.

Where the Truth Lies explores the dark and destructive side of showbiz

success. Vince Collins (Firth) and Lanny Morris (Kevin Bacon) are the

hottest showbiz partnership in 1950s America. When a beautiful young

woman is found dead in their suite, their world falls apart. Fifteen

years later, a journalist persuades a publisher to offer Collins $1m to

collaborate with her on writing the untold story. Through a variety of

conflicting accounts, the mystery is grippingly sustained until the

movie's end. The sex scenes, featuring Bacon and Firth together in the

same room as assorted young women, were anything but sexy, Firth

reports. "We ran through the morning with our curlers in. Then we ran

through it partially clothed, sorting out where the guy with the boom

microphone was going to be. Hopefully, not anywhere near me: it takes

all the sex out of it."