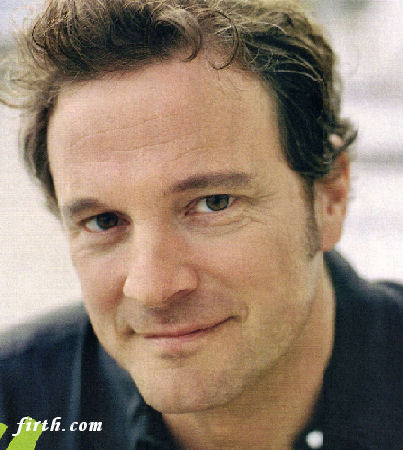

It's a drizzly morning in Santa Monica. Worse, a car nearly clips British actor Colin Firth as we cross the steep on-ramp that leads down to PCH. Not the most auspicious start to an interview. But Firth, in a display of sangfroid worthy of types he frequently portrays onscreen—we might call them reserved, he has described them as “quintessentially repressed”—never breaks his stride. His conversation doesn’t skip a beat either. “It’s nice to (a) walk in this city and (b) walk in it when it’s raining,” Firth, 47, says. Mark Darcy, the lawyer he plays in the Bridget Jones films, couldn’t have put it more judiciously. For our walk from his hotel, Casa del Mar, to Palisades Park, Firth has exchanged the modish bomber jacket he was wearing when we met for a weather-appropriate windbreaker. He still looks surprisingly boyish. Where his characters are ponderous, he’s lithe: more open-collared casual than stuffed shirt. Although he lives in London, he clearly has a soft spot for Los Angeles. He describes the thrill of his first adult visit to the city, during which he stayed at the Tropicana Motel, then home to Tom Waits, and the house he later rented in the wilds of Malibu. But the irony Britons often acquire along with their accents is never far away. “One of the things I do believe is absolutely unique in this town is what they call ‘hiking,’ ” he says. “You know, the morning walk up the hill somewhere. I was invited on one a couple of years ago. I found it an eccentric suggestion, but then I ran into everyone I knew.” His purpose this trip involves another local eccentricity: motion capture. That’s the computer-aided phenomenon by which live actors become animated enhancements of themselves. Firth will be working with Robert Zemeckis (the director whose Beowulf turned Angelina Jolie into a slinky seven-foot monster) on a remake of A Christmas Carol. The film features Jim Carrey in multiple roles as Scrooge and the ghosts of Christmases present, past, and future. With Carrey snapping up all those parts, whom does Firth play? “I’m Fred,” he says. Pressed, he describes Fred as the cheerful nephew. “He’s the guy who won’t give up on his uncle. Nobody seems to remember him, and I doubt I’ll do anything to change that.” He may be too modest. Jane Austen was not considered a huge box-office draw until Firth’s performance as the snobbish but meltable Mr. Darcy in A&E’s 1995 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice made him a transatlantic heartthrob. (The same role—uptight but upright—was the basis of his character in Bridget Jones.) This spring he appeared in Then She Found Me (Helen Hunt’s directorial debut) as the fiery single-father love interest of Hunt, an adoptee determined to have her own child. (That agenda is not entirely strengthened by encountering her birth mother, a motormouthed talk-show host played by Bette Midler.) Firth gets his shot at portraying a conflicted middle-aged child in When Did You Last See Your Father?, opening this month. Based on the prizewinning memoir by British author Blake Morrison, the film, directed by Anand Tucker, examines a son’s ambivalent relationship with a dying but still larger-than-life parent. Firth’s own mother and father are alive, and he speaks of them affectionately, but he says the film roused powerful emotions. Later this summer he’ll star in the movie adaptation of the musical Mamma Mia! alongside Meryl Streep, followed by The Accidental Husband with Uma Thurman. We have reached the Broadway end of the palm-shaded park, site of our destination, the Camera Obscura. Firth looks faintly alarmed. Most tourist hot spots don’t involve dodging a clutch of aluminum walkers in a busy senior center. A century ago when these optical devices were popular seaside attractions, this camera—essentially a room with a periscope in its ceiling—was housed in its own cottage in the park overlooking the pier. Today the only entrance is through the center’s lunchroom and up a flight of stairs. The camera is no place for the claustrophobic: In the darkened room nothing is visible except a huge, waist-high, seemingly floating image of the world outside—palms, sand, Ocean Avenue motels.  In

his role as the Dutch painter Jan Vermeer in Girl with a Pearl Earring, Firth

demonstrated a box-size version of a camera obscura to a dazzled

Scarlett Johansson. The actor, still in his diffident mode, claims his

research “has really all gone out of my mind.” He then proceeds to

explain that the movie device was probably misnamed, that it was based

on a machine invented by a friend of the painter’s, that Vermeer didn’t

copy the image projected by the lenses but used it as an instrument of

perspective, that the image we are seeing here is reversed, and that

lenses, hence photography, make people look closer than they are. He’s

been pacing as he talks, unfazed by the dark, and has discovered the

captain’s wheel that swings the rooftop periscope in a 360-degree arc.

One twist, and the world at our waists is spinning. “That’s more

exciting,” he says. In

his role as the Dutch painter Jan Vermeer in Girl with a Pearl Earring, Firth

demonstrated a box-size version of a camera obscura to a dazzled

Scarlett Johansson. The actor, still in his diffident mode, claims his

research “has really all gone out of my mind.” He then proceeds to

explain that the movie device was probably misnamed, that it was based

on a machine invented by a friend of the painter’s, that Vermeer didn’t

copy the image projected by the lenses but used it as an instrument of

perspective, that the image we are seeing here is reversed, and that

lenses, hence photography, make people look closer than they are. He’s

been pacing as he talks, unfazed by the dark, and has discovered the

captain’s wheel that swings the rooftop periscope in a 360-degree arc.

One twist, and the world at our waists is spinning. “That’s more

exciting,” he says.Firth’s success in portraying archetypal Englishmen may come in part from his own less than insular perspective. He’s seen them from both sides. His father is a history professor whose specialty is the U.S. civil rights movement. His mother, a missionary’s daughter, grew up in India and Iowa, while his own childhood included stints in Nigeria and St. Louis. The latter, he says as we exit the senior center and head toward the beach, coincided with the Watergate hearings. “Not the most exciting experience” for an adolescent, he says, but thanks to his father “I got quite fascinated in the process and the way this country has always been prepared to arraign its leaders if they see something that’s not right.” There’s an uncomfortable pause. “Well,” he says. “That’s something they’re going to have to get back again.” At home in London Firth practices the engagement he preaches. He and his wife, documentary filmmaker Livia Giuggioli, recently opened Eco, a West End shop dedicated to fair-trade products and energy-efficient strategies. They also produced the film In Prison My Whole Life, about former Black Panther Mumia Abu-Jamal, who is on death row for the 1981 murder of a Philadelphia policeman. “What interested me,” Firth says, speaking of the film’s writer, William Francome, “was this young man’s desperation to see if he could answer some questions about the political climate that surrounds a case like that. So many voices we hear from are so embedded in a position on either side that it’s very difficult to get any clarity beyond the passion and the emotion that the subject raises. That doesn’t give us [as Britons] any authority; it just gives us a different view.” Firth’s upbringing was not all an outsider’s. As a child in England he lived in leafy Hampshire, “just down the road” from Jane Austen’s former residence at Chawton. Although he claimed earlier in the day to have a “numb spot” where Austen is concerned, walking has thawed him on the subject—as the novelist herself might have predicted. “They showed what she wrote on,” Firth says, “and it’s a little round lamp stand. I mean she had bits of paper, and she sat in a small armchair, presumably leaning slightly to the left and scribbling.” He talks faster, imagining the scene. “In some ways it’s a test of her integrity. She didn’t write what she didn’t know. There isn’t a single conversation between two men alone in a room in her entire oeuvre.” The expertise that comes from insider knowledge has its charms in the movie business, too. For Firth, a highlight of making Then She Found Me was working with a director who is also an actor. “I don’t think anyone understands the job unless they’ve done it, who knows what the traps are that actors get themselves into,” Firth says. “An actor knows where the bullshit is—‘That’s a little mask you’re in, that’s an insecurity you’re displaying.’ ” Firth has been reading Ask the Dust, John Fante’s novel of 1930s L.A. He was struck by the desperation of Fante’s writers and actors and, he says, “the massive expectations to succeed. There’s no point in even telling people back home about any disillusionment—they’ve seen the pictures, they’ve seen the sunshine.” As if on cue, the clouds thin. Casa del Mar is just ahead, its stately facade rising above the narrow street like an image from a noir film. “It’s amazing how much history there is in such a short space of time in a place like this,” Firth says. He’s not just referring to this ambience-drenched block. “I could live on American culture alone,” he says. “I mean I’d miss an awful lot of other things, but just let me have blues and jazz and American movies and American literature; I wouldn’t consider myself impoverished.” The accent may be English, but the enthusiasm is almost Californian. For Firth that’s proved to be the best of both worlds. |