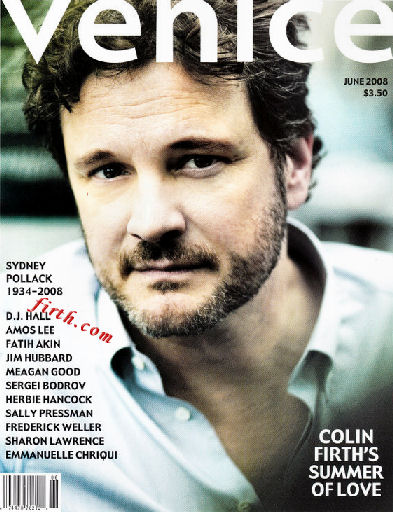

There’s something to be said about an English accent when it comes to melting American hearts, especially when it’s delivered with the comically uptight precision of Colin Firth. Continuing a lineage of romantic Brits that has stretched from Cary Grant to Hugh Grant, Firth has made women swoon in such films as Valmont, Love, Actually, Then She Found Me, and two Bridget Jones films—even if he loses the girl to the more dashing likes of the Fiennes brothers. Yet if cinematic love has a way of evading Firth, he’s always handled the “other guy” task with intelligent distinction and the kind of wry humor that’s made him one of the best leading men in the romantic biz on either side of the Atlantic. This summer, he’ll be battling again for the leading ladies, trying to prevent radio personality advice queen Uma Thurman from being captivated by Jeffrey Dean Morgan in The Accidental Husband, and then doing an Abba sing-off for Meryl Streep in Mamma Mia! alongside fellow golden throats Pierce Brosnan and Stellan Skarsgård. While Firth has mastered chick flicks with reserved aplomb, he’s been just as prolific in films that go for the mind and the heart. Making his first major film appearance as an unbalanced cineaste in 1989’s Apartment Zero, Firth’s impressive “art” resumé includes playing a Medieval advocate in The Hour of the Pig, appearing in the David Lean (sic) miniseries “Nostromo,” painting as Vermeer in Girl with a Pearl Earring, and doing a twisted spin on Dean Martin in Where the Truth Lies. But for pure, gut-wrenching power, Firth’s new role as a poet with major dad issues in And When Did You Last See Your Father? is at the top of the list, as his character must put his dysfunctional demons to rest to make ultimate peace with his raucous father (wonderfully portrayed by Jim Broadbent). If Colin Firth’s most populist work has women reaching for their handkerchiefs, then his Oscar-worthy performance here is likely to do the same to any man who wished to be a better son. Born in 1960, the offspring of parents who specialized in history and comparative religions, it’s not hard to see where Firth’s intelligent charisma would spring from, even as the family’s early travels took Firth as far afield as Nigeria. Returning to England at the age of five, Firth would later study acting at the Drama Centre in Chalk [Farm], where his performance as Hamlet would lead to his first professional stage role in “Another Country”—whose film version counted as Firth’s bigscreen debut. Building stage credits as a member of the Royal Shakespeare Company (sic) alongside such celebrated British television roles as Darcy in “Pride and Prejudice,” fueled Firth’s full-fledged leap into feature films. With some of his most adventurous movies and characters in the offing, Colin Firth reflects on a career that’s ranged from wearing Victorian costumes to wielding Roman swords, and belting out Abba songs on a Greek island, all with a self-aware humor that comes from a creatively charmed career. Tell us about your character Harry Bright in Mamma Mia! Before I’d even figured out who my character was, I tried making heads or tails out of the script, which was hard to read with Abba’s lyrics in it. I mean, you’d get two lines of dialogue, and then someone says, “How can I resist you?’ from the song “Mamma Mia!” I told our director Phyllida Lloyd that I didn’t have the faintest idea what sort of person I’d be playing with Harry. So before I accepted the role, I went to see the musical on stage, and only then did I realize what a feat of contortion it was to work all those Abba songs into a single story. Yet all those tunes fit here—all except for “Fernando,” which is about a soldier in South America. And there’s no way you could put that into the story! We were talking about an exuberant piece of musical entertainment, and I didn’t want to de-construct it too much, especially with Harry’s character. He’s a nice man who’s gotten bored in life. He’s become very successful, yet still isn’t happy. One of the things he always wanted was a daughter, so he’s eager to accept that relationship when it occurs to him that maybe he has one. Had you sung before doing Mamma Mia!? I’d always been, how shall I put it, an “optimistic singer.” I’d enjoyed doing it but at the same time I’d always been cautious of inflicting my voice on anybody. When I’d sung in a band as a student, I don’t think anybody really thanked me very much for doing it! Before Mamma Mia! the only other film I’d actually done any singing for was The Importance of Being Earnest. Rupert Everett and I had a light-hearted ditty that was an Oscar Wilde poem put into lyrics, which we performed as a serenade. Do you have any solos in Mamma Mia!? Well, I do sing solo in the film, but, mercifully, I don’t have an entire song to myself, as the others come in and save me at the choruses. But I’d say that “Our Last Summer” is basically Harry’s song. I’m blessed with its being one of the lesser-known Abba tracks, because it was on an album instead of being a single. Yet it’s actually one of the nicer songs, I think, even if I can’t claim to be an Abba aficionado. Straight males of my generation usually weren’t, and aren’t. But it’s a pretty song that’s not hallowed ground, or over-familiar. So the people who see me as wrecking an Abba song will be hopefully less than if I’d been given “Dancing Queen.” What was more difficult to do in Mamma Mia!—the singing or the dancing? Oh, nothing is more difficult for me than dancing—in anything! It was a horrendous spectacle, really. But I wasn’t alone in that with Pierce and Stellan. We were three middle-aged guys, realizing that they didn’t cast John Travolta, Patrick Swayze, Kevin Bacon, or all of these people they knew full well could dance and act. They needn’t ask us if we could do that, so they’d get what they’d get, but we did our best. And if there are any horrors in the dance moves, then we have to comfort ourselves that this is also a comedy. The other romantic comedy you have coming out this summer is The Accidental Husband. Do you think you were essentially doing a 1930s screwball romance with this film? I think it was definitely, unashamedly genre. There is something sort of vintage about the film, and it does doff its hat to the old, classic comedies. You’ve made a name for yourself doing these slow-burning, romantic suitors. The “other guy,” if you will. How do you keep these kinds of parts fresh for yourself, especially in The Accidental Husband? That is actually the burning question that comes before you all the time, and it’s not just about comedy. There’s a version of everything you’re being asked to do out there, somewhere. And the chances are that it’s already in your own repertoire. So your job is to make the role as specific as you can. Don’t worry too much about originality, because people get themselves into knots looking for it. You just have to do the part as truthfully as you can, and if it’s specific, then it’ll be fresh and unique to you, but I think that’s the job of an actor anyway. You’re starting off with someone else’s words, and you have to make them seem new again instead of lying there flat on the page. You’ve got to animate it. And even if it’s the most surprising and unusual role you’ve ever played when you get to filming, it’ll still get old after the fifty shots you’ve done by day three. But even if you’re constantly wearing yourself out, you still have to breathe life into your work. And if it goes well, and you’re lucky, the words and your character will come alive with the spontaneity you’ve been looking for. How do you think Uma Thurman stands out among your romantic leading ladies? I think she’s wonderful. And she certainly stands out, especially among the great blur of actors you encounter in film, television, or the theater. Some of them are talented and some less so. And every so often, someone burns themselves into your memory. And the minute I first saw Uma in Dangerous Liaisons, I was impressed with how beautiful, powerful, articulate, and intelligent she was. Uma’s got a lot going for her, and she has an amazing presence on the screen.  Is

there a trick to playing “the nice guy” who’s often bound to lose a

woman like that? Is

there a trick to playing “the nice guy” who’s often bound to lose a

woman like that?I think you’ve got to take words like ‘nice’ and ‘not nice’ out of it when you play a character, because they’re unhelpful judgments. They’re just casual evaluations other people make. You’ve just got to see what’s going on with the character, and find a way in. It’s not going to help you if you’re playing Genghis Kahn (sic) and you start off playing him by saying ‘He’s not nice,’ You’ve got to make your own decision about what motivates him. Maybe he’s just a big coward or insincere on some level. It’s interesting to find those motives which is how you flesh out any character. Are you surprised that you’ve become this romantic start in Hollywood? I wouldn’t have put it that way because I don’t know if I’ve truly reached that point. But I am surprised that the romantic tag has followed me through my 30s and 40s even if I know it’s not unusual for men to still be playing that beyond my age. I was surprised to get a role like Pride and Prejudice’s Darcy at the ripe old age of 35. And maybe that’s one of the things that encouraged me to do more of these kinds of parts before moving into character work. So if the association is still going on, then yeah, it’s surprising. But when you do something, especially on television, then it’s going to make its mark. People don’t let you forget it. And that’s absolutely fine with me because it’s absurd to resist that. I’m just surprised it’s still with me. What older stars have you modeled your romantic abilities on? I don’t think I’ve modeled myself on anyone in particular. I’ve just pillaged and foraged from bits and pieces of every actor I’ve admired. Whenever I’ve been captivated by an actor, I’ve scrutinized why they have such a fascinating and likable effect on me. I’ve always admired the intelligence, humor and ease that Spencer Tracy had in front of a camera. Paul Scofield was a great example to me when I saw A Man for All Seasons as a kid. He had this quiet integrity. Until then, I’d always been impressed by these big displays of pyrotechnic acting, these huge transformations. The more “acting” there was, the better. And suddenly, here was this man who seemed to do so little. It seemed to come from some place inside of him, and that was an introduction to me of what the real possibilities of acting were. I also love John Hurt, Anthony Hopkins, and Peter O’Toole. I’ve tried to copy all of them at one point or another. And even if I succeeded, it wouldn’t look the same on me as it does on them. You give an amazingly emotional performance in When’s the Last Time You Saw Your Father? (close enough) Did you draw on your own personal relationship for the film? You don’t have to dig too far, because those issues are so alive in all of us. It amazes me that there aren’t more films about fathers and sons, or mothers and daughters, for that matter. Your relationship with your parents is a big part of our lives. Everyone’s got issues with their father, and if they don’t, then they have issues with not having one. So that figure is of immense importance, because everyone’s going to lose that person, or they already have. That creates a very universal theme for us, and because it’s so universal, you have to find a way to make it specific, because otherwise you’re going to be telling people what they already know: That their dad dies, and it’s sad. But what sets Father apart is it’s honest about the inadequacies of the grieving process, how difficult that is, and how no one’s prepared for it. It doesn’t happen the way you planned it, and you don’t cry on schedule. You don’t say all the things you wish you’d said at the right time. And sometimes you have negative feelings towards the person you love, and you carry that after they’re gone, and you feel guilty about that. Father deals with all of those things. It’s difficult to know if what I’m saying is a pitch for the film or not, because some people will say they don’t want to go near a movie like this. So you can only try to convince them that this isn’t a long catalogue of unhappiness. Father actually takes you through the stuff that’s difficult without giving you trite resolutions. Anyone who’s had difficulties with loss, or just dealing with their parents, is going to find that this film isn’t sugarcoating anything. You’d worked with Jim Broadbent before, most noticeably in the Bridget Jones films. Did that give you an instant relationship you could draw on here? Jim and I don’t know each other intimately, but it certainly did help that we’d worked together a few times before this. I’d just done a film with him before we made Father. So it was great to have somebody that you can twinkle with when he walks into the room. And because I already had a history with him, it mattered enormously to our characters’ relationship here. Because the older you get, the more likely you are to find that, and the odds that actors will encounter each other again gives you a real shorthand. There’s an incredible moment at the end of the film where Blake is truly hit with the loss of his father, and begins to weep uncontrollably. How did you draw that out of yourself? I’m not sure that we even had that moment, actually, and I’m not sure if it should be in the film. When I watch that scene, I keep questioning it, especially since the director stops all the music there. That allows the emotion to be very exposed, yet I feel there’s something about that crying scene that isn’t quite the big outpouring of grief that it should be. There’s still something a little constipated about it, and I think that’s probably right not to open up Blake’s floodgates, especially since he’s previously complained that he can’t cry over his father’s loss. One of my favorite thrillers is Apartment Zero, which was a real breakthrough performance for you in America’s art cinemas. It certainly was in the States, though I’d done two other projects in England that I felt had the same effect for me at the time. One was called “Tumbledown,” which was a BBC drama that didn’t get a theatrical release in America, though it’s just come out again in England on dvd. Doing “Tumbledown” was an amazing experience, because I played a boy who was my age, in a real story about Robert Lawrence, a soldier who was shot in the head in the Falklands War. He suffered a severe brain injury that caused paralysis down the left side of his body. I got to know Robert quite closely, and worked with him every day on the set. So it was odd to make a film about our recent war with Argentina, and then to go and make Apartment Zero there. I don’t really know what genre you’d put Apartment Zero in. It takes a bit from film noir and has a streak of camp about it as well. There have certainly been echoes of my character in Zero that has recurred since. There was also another film I did during that period called A Month in the Country, which was about war and recovery, set during World War One. So there was a cluster of three things that I feel immensely proud of. All were made during an intense time in the late 1980s, and I was very idealistic about my profession in those days. Your first true “Hollywood” breakout was Milos Forman’s Valmont, which told the same story as Stephen Frears’ Dangerous Liaisons—only a year later, in 1989. In spite of that, I’ve always thought that Valmont was the better telling of Les Liaisons Dangereuses. Well, I’m not going to comment on that, but it was an unusual situation. We were filming at the same time as Dangerous Liaisons. It’s the kind of bizarre situation that doesn’t happen very often, like when they made all those Robin Hood movies. Milos Forman had wanted to do this for a long time. He’d talked to the play’s author Christopher Hampton about doing it, and the project just diverged into two at some point. It was bizarre, because everyone knew we’d be in competition with another film. We took six months to film Valmont and then it took even longer to come out because Milos likes to take a long time to edit. So Dangerous Liaisons already had Oscars by time that Valmont was released. We were in a very disadvantaged position. It was a bit like walking into a room where someone had just told a joke, and the laughter was dying down. Then you tell your joke and it’s the same one. You might think that you’d told it better but it doesn’t really matter because people had already heard it. But viewers who do catch up with Valmont now, love it. They just needed that separation from the time they’d seen Dangerous Liaisons to appreciate this version. Miramax always had ingenious marketing in the ‘90s, and when they released The Advocate, which used to be called Hour of the Pig, they urged audiences not to talk about who your character’s “client” was. It’s certainly one of the most unusual Medieval courtroom dramas to be filmed. I also think it’s one of the most interesting scripts I’d ever read. Leslie Megahey made it. He’d spent nearly twenty years as the head of music and arts at the BBC and was quite a Renaissance man. Leslie has a very particular take on certain pockets of history, and finding absurd moments with which to view society. He sees them as a prism of how we look at ourselves—not just in the past but how they also reflect our present-day absurdity not to sound too lofty about it. Leslie had done a television film called “Schalcken the Painter.” It’s a ghost story built around a relatively obscure Dutch painting and it’s incredibly eerie. “Schalcken” is one of my favorite movies ever made. Leslie also made a definitive documentary about Orson Welles. He was a very interesting guy to work with on Hour of the Pig and I’m very proud of that film. You worked with the late Anthony Minghella on The English Patient. What’s your best memory about him? My greatest memory of Anthony wasn’t from The English Patient, because we were friends for a long time already. I met him when I was 25 in Manchester, doing a radio version of one of his plays called “Two Planks and a Passion,” in which I played Richard II. It was about the staging of a Passion play in Medieval York. Anthony was then a writer for the stage. I stumbled on his work in a provincial theater, and thought it was wonderful. So when I was sent this script. I was already a fan of his. Anthony and I became friends while doing “Two Planks and a Passion.” He drove me back to London, which took two or three hours and we talked about everything. Anthony introduced me to all kinds of poetry that I hadn’t been aware of. We also had a connection because I’d discovered Pablo Neruda, whom Anthony was also a big fan of. So this wonderful trip was two pretentious people bonding! One of the more complex roles is in Where the Truth Lies, where you essentially give a homoerotic spin to Dean Martin in your relationship with Kevin Bacon’s ersatz Jerry Lewis. When the director Atom Egoyan first sent me the script for Where the Truth Lies, he said, “You’ll think it’s Lewis and Martin, but that’s not what we’re doing. This might be a comedy act in the 1950s that’s somewhat like Dean and Jerry.” I mean, you could just imagine the legal problems we’d have if we were trying suggest that these known characters were hiding a crime like this! Also, I played an English gent, where Dean was Italian-American. My character’s backstory was that he was a total phony, a guy with an English shtick. So I looked through history to see who existed like that guy. Who is it that imports English shtick into Hollywood as a kind of cabaret? So I thought what if Vince was a little bit part Peter Lawford, part Cary Grant, and a bit Noel Coward? So Vince wasn’t quite anybody in particular. And I think my character is the weaker, and less talented of the two. He’s the one who suffers the most when his partnership with Lanny breaks up. Vince becomes a matinee idol for a few years, but even that starts to fade. I found that a fascinating story, the whole idea of living with a horrendous secret when you’re under that kind of scrutiny. And I love how Atom put me in a big glass house, a millionaire movie star lives on teh top of a hill in a house with windows everywhere. He’s isolated and alone, but on show as well. I thoroughly enjoyed The Last Legion where you really got to step outside of the box and play a Roman soldier. What was it finally like to be in a sword and sandal movie? I enjoyed making it as much as anything I’ve ever done, though Mamma Mia! does come pretty close. I think all of us who were in it still imagine that we’re fifth century Roman soldiers! We’ve remained great friends. Just don’t let your imagination run away with what that would look like! It did feel a bit old in the joints to be swinging a sword at my age though. I wish they’d come to me with this part when I was 25! One of your first performances was in a Christmas pageant as a child, and now you’re doing a motion-capture version of A Christmas Carol with Jim Carey (sic) for director Robert Zemeckis. Do you think your career has finally come full circle now? Doing films like A Christmas Carol take me back to the kind of stories that first made me want to do theater, and get into films. I had a wonderful time doing a similar film called Nanny McPhee. It was just wonderful seeing kids respond to that, even if I didn’t think I wanted to do kids films at first. Yet when you see audiences get so much pleasure from movies like Nanny McPhee, you realize that this is where the magic of wanting to be an actor really starts. There’s nothing more satisfying than reaching kids. I think “A Christmas Carol” is still one of the best stories ever, one that all audiences can appreciate. It gets the old hankies coming out at the end. I only wish I’d had a bit more time to be involved in A Christmas Carol actually. They got me in and out in about two days. You’ve made a good career doing the romantic leads that people expect of you, but also appearing in as many intelligent art films as well. Was this a path that you always planned on? I didn’t map my career out that way, but I quite like that’s worked out that way. Peter O’Toole used to say, rather archly to me, “One for show, one for dough, darling!” It doesn’t seem like a bad way to go if people are allowing you to do that, especially since it’s so difficult to get small films made. And if you’ve got some profile that you’re carrying over from the bigger films, then it helps. I think a lot of actors try to do it that way. I listened to George Clooney being interviewed recently, and he said, “I’m really glad that my sell-outs haven’t really been so bad. I think they’re OK, and it’s helped me pay for the stuff that I really want to do.” That kind of career approach has definitely served me well on a different scale. I’ve read that you and Hugh Grant have an amiable rivalry when it comes to being “the” English romantic lead in Hollywood. If you could compare this to the legendary catfighting between Joan Crawford and Bette Davis, which actress would you be? Oh God [laughs] I would probably say that I’m capable of confining Hugh to a wheelchair and serving him rats. Let him take the Joan Crawford role. |

||

|