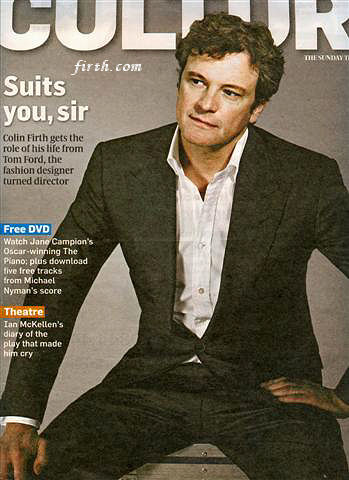

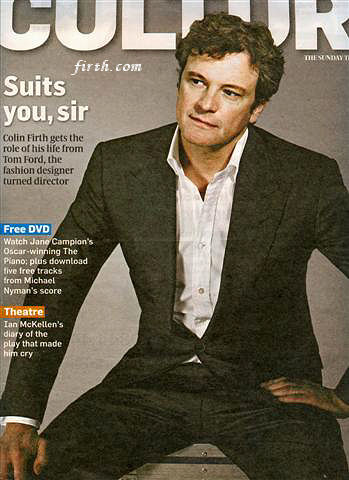

Tom Ford and

Colin Firth join forces for A Single

Man

A Single Man stars Colin Firth and

sees fashion designer Ford turn his hand to directing—with spectacular

results

|

|

Christopher

Isherwood’s 1964 novel A Single Man

concerns George, a gay, English, 52-year-old professor in California,

who is bereft after the death of his lover. As he ponders the

possibility of suicide, he starts to see the world afresh,

transforming this into a story of beginnings as well as endings.

It is fitting, then, that the men who have been instrumental in

reimagining Isherwood’s book for cinema should find in the process

their own kind of rebirth.

Not that either wants for success. The 49-year-old Colin Firth, who

plays George, is cherished for the poignant and humorous understatement

he brought to hits such as Mamma Mia!

and the Bridget Jones films, although his versatility is demonstrated

well in less familiar works such as Where

the Truth Lies, in which he played an unsavoury singer, and the

Falklands drama Tumbledown.

His performance in A Single Man

is one of stunning range: he brings to life George’s

merry-cum-melancholy friendship with a colourful English

divorcée, Charley (Julianne Moore), his cautious fascination

with a campus dreamboat (Nicholas Hoult) and the contentment of life

with his late lover (Matthew Goode). Firth took home the best actor

prize from last year’s Venice film festival; the forthcoming Oscars

will surely be a laughing stock if his name is not among the nominees.

While Firth is at the top of his game, the 48-year-old designer Tom

Ford is jumping disciplines. This colossus of fashion brought Gucci to

its current prominence (he joined the company in 1990 and began his

decade-long tenure as its creative director in 1994). Ford, who now

presides over his own eponymous fashion house, had long had his

antennae out for the ideal film project. The confidence he exhibits in A Single Man, which he directed and

co-wrote, makes it clear he found it: every detail is right, from the

lush score and the 1960s costumes and architecture to the vision of a

sun-baked Los Angeles, watched over by Janet Leigh from a vast Psycho

billboard.

Actor and director joined me in a London hotel room to pick over the

details of their collaboration. Firth came dressed for comfort in

jeans, trainers and a baggy grey sweatshirt. Ford, on the other hand,

wore a charcoal suit, a grey tie and glinting cuff links. With his

short hair like black ash, and a beard trimmed so close, it could have

been pencilled on, he exuded wealth. (One splash of his cologne would

probably cost more than the entire hotel.) What became apparent during

our conversation was that the men enjoy an easy rapport and harbour a

genuine love for the film they have made together.

Ryan Gilbey: Colin, did you receive your prize at

Venice with typical British embarrassment?

Colin Firth: Actually, I

didn’t at all. I had a particular connection with Italy anyway, as my

wife is Italian, so that added to the joy, the charm, of the moment. It

didn’t just feel like any old gong, put it that way. My wife’s family

took me on trust 15 years ago, so for them it was a special moment. I’d

shown up as this very, very dodgy commodity, attached to their darling

daughter. When we got together, she told them, “I’ve got this English

chap now”—one strike against me. “He’s an actor”— hmmm, oh, dear. “He’s

nearly 10 years older”—oh, boy. “And he’s got a kid with someone else.”

I had a mountain to climb to win everyone over. So to be standing there

with the award—well, everyone in Italy knows what that award means. And

I had enough of the local lingo to express how I felt; there’s no other

non-English-speaking country in the world where I could have done that.

Was Colin your first choice for

the part, Tom?

Tom Ford: Absolutely. But

when we were first supposed to be shooting, he was tied up making Dorian Gray. I remember talking to

him at the Mamma Mia!

premiere. It was so frustrating, because I’d had to cast another actor,

and here I was, talking to my first choice. I got in the car afterwards

with Richard [Buckley], my partner of 23 years, and I just said, “F***,

f***, f***. Goddammit.” Then our shoot got pushed back, Colin became

available and things magically came together.

If you swear enough, you often

get what you want.

Firth: You can swear them

into place, that’s right. I remember Tom staring at me at the premiere.

Ford: I think you thought

I was flirting.

Firth: [Laughing] It wasn’t that kind of

stare, it was much more enigmatic. What was great was that Tom had this

personal and complex story he wanted told, and to have him put that

whole thing in my hands was a chastening responsibility. It’s the sort

of thing that makes you think, “Okay, I’m going to have to raise my

game for this.”

Ford: I knew the

perception from the outside world would be that I was a risk.

Firth: But Tom’s not got

a record of screwing things up.

If you’re successful at what you do, and you’re gainfully employed, the

risk can be that any sense of the unexpected flies out of the window

and the whole thing becomes a treadmill. It shouldn’t be like that. The

privilege of having a profile, of getting to work as we do, shouldn’t

be allowed to be squandered. And this came at a moment when I

absolutely needed something bracing and refreshing. For it to be Tom

excited me. The script wasn’t ordinary, either.

In what way?

Firth: It was clearly

highly intelligent. There was an emotional potential that wasn’t

explicit, which was exciting to me, because I’m there to fill in the

gaps. I remember early in the shoot, I was glancing through another

script I’d received. A perfectly good script, but it just felt —

ordinary. That’s when I realised, “This one’s going to be special.”

Tom, it’s interesting that

Colin mentions the “gaps”. Some of the most powerful moments, I felt,

simply involved him staring into space.

Ford: Yes. There are so

many points in the film where George is internalised; we needed to see

on his face, in his eyes, what he’s feeling and thinking. Colin is

amazing at that. It was often hard to say “Cut”.

What are you thinking in those

moments, Colin? Are you thinking George’s thoughts?

Firth: [Thoughtful] Yes. I mean, as much

as that’s humanly possible. If someone shouts “Fire!”, then I’m out of

the building. But as much as that subjectivity is possible, absolutely.

And I think the relationship between actor and director is critical

here. If you work with the wrong director and you’re my sort of

actor—well, you’d miss it, really. I don’t enjoy highly demonstrative

stuff, and for me to be thinking George’s thoughts, and for Tom to be

able to read it, meant that the relationship was working. I felt quite

quickly that Tom wasn’t cutting when I expected him to cut. So I could

sense someone on the other end. I knew it was getting through.

How did that feel?

Firth: It was kind of

galvanising, motivating, inspiring. It made me think, “Right, there’s

more to go for now. I can see the world in a certain way, and he can

see what I’m seeing.” Also, I’m feeding off what Tom’s set up. The

eloquence of the design, costumes and locations was so helpful. And we

had that house, which told me a lot of the story. It’s a cosy wooden

structure surrounded by trees, but it’s also glass, so it’s exposing. I

walk on set and I see where the camera is. It’s outside, looking into

the house, and it’s just going to be me at that table with a coffee,

and the phone will be ringing. That, for me, is already resonating: I

know it’s not going to be a scene about a happy guy setting off for a

party.

Ford: George is destroyed

inside, so he’s holding himself together, clinging to these physical

things—the house, the clothes. He probably had his suits made on Savile

Row. So we had those made, and we had the name “George Falconer” sewn

inside. You never see the inside of the suit, but it’s all there. I

think those things are incredibly important to an actor. Yes, it’s a

beautifully cut suit, but it’s brown tweed because he’s a professor.

Firth: That’s the sort of

thing I was driving at. The suit told me who George was. There’s

nothing like unspoken communication in any collaboration. And on this,

thankfully, there were no executives in the background. There was no

machinery behind it. What happens when there’s a lot of money at stake

is that the producers get involved. They won’t come to you, but they’ll

speak to the director. I’ve had that. Absurdly—and I’m not normally the

one to bring this up voluntarily— when I was playing Darcy [in Pride and Prejudice], some

executives were alarmed that I wasn’t brooding enough. But we’d been

shooting the later stages first, when Darcy sort of lightens up. I knew

we still had to shoot episodes one to four, in which I was going to do

nothing but smoulder and look out of windows. It was ridiculous. I

mean, I’d read the damn thing.

Tom, I liked the way George’s

situation is mirrored in the other people in his life. Everyone’s at a

crossroads here, aren’t they?

Ford: Yes, all the

characters are going through change. Charley, for instance, can’t see

her future, just as George can’t imagine his. That’s why they’re drawn

to each other. They’re book ends of the same character. A lot of women

I know today, they play by the rules, they do what’s expected of them,

then they end up stranded, like Charley. Men have this well-publicised

midlife crisis—leaves his wife, buys a fast car, dates a blonde—but

nobody addresses what happens to women in our culture.

There’s clearly great affection

in the film for all the characters. It has been said that a director

looking through the camera at an actor can feel something like love.

Did you find that, Tom?

Ford: Of course. You have

to have a crush on every single one of your actors. But they’re also

portraying a character— which, in this case, I wrote—so I had a crush

on the characters anyway. I said to Colin, “I have such a crush on

you.” Now, I have a crush on Colin in real life. Who doesn’t? But

that’s not the crush I was talking about. I had a crush on Colin as

George. I felt the same way about Julianne. You need to love your

characters.

Were you conscious of avoiding

the archetypal portrait of the gay man as victim?

Ford: I never wanted him

to feel like a victim. Besides, it’s not a gay story, he just happens

to be gay.

Firth: It was very little

in my mind. I could almost say that, while we were filming, I’d

forgotten that “gay” was one of the epithets you could apply to this

character. It’s about solitude. And if you change the love interest to

a woman, you could still make the same film. The moment when he’s asked

not to come to his lover’s funeral—that could be any secret or

inappropriate lover.

Ford: It could be an

English actor with an Italian family.

Firth: [Laughing] Well, quite. There was a

whole big fold that was closed to me until I got hitched and was

wearing the ring. There are other things aside from being gay that can

isolate you. George makes a big speech about fear, and he identifies

that as an invisible threat in society. He’s right. Fear is a useful

commodity. Get enough fear out there and you can do what you like—set

up a Guantanamo Bay, invade any country.

Ford: You can feel the

fear every time you open a fashion magazine. You look at the models and

the clothes, and you feel you're a disaster, or you’re not up-to-date

enough.

But don’t you perpetuate that

fear, Tom, by working in the fashion industry?

Ford: Of course, and

that’s something I’ve had to deal with and justify. I think if you keep

it in perspective and realise that, yes, we may have a soul and an

essence that are not of this world, but we still feel things and touch

things, then you can allow yourself to enjoy those things. They add

value to the physical side of your life. But you’re right. I don’t know

how to justify it. I get an enormous amount of pleasure from visual

things. I come into a room like this and I immediately want to

rearrange the furniture. That’s what the film is about for me—getting

lost in the physical world and losing touch with the spiritual, which

is certainly something I’ve experienced.

Firth: What’s strange, to

me, is that George has haunted me since I stopped doing the film. I

feel he’s around somewhere. I have this slightly irrational thing that

happens when you fall for a fictional character—I keep thinking I’m

going to run into him somewhere. I want to check in on him, wherever he

is, and make sure he’s okay.

|