The Beating

of McCarthy

Following last year's

climactic release of Western hostages

in Beirut, a controversial new docu-drama beats

John McCarthy to his own story. Andrew Billen talks to

actor Colin Firth about his role as the captive journalist.

|

|

During the long

incarceration of the Western hostages in Beirut, we must all have asked

ourselves the same questions. Could we have coped? Would we have lasted

the course, and if so, what shape would we be in at the end? Would the

truths we had learnt about ourselves not have shattered that fragile

arrangement of instincts and artifice that our friends and family

recognise as our personality?

The loneliness, the sensory deprivation, the physical torture of

beatings, the psychological torture of not knowing from day to day

whether you were going to be released or executed made the ordeal of

hostages a late 20th-century version of hell. Except that the cells

they were held in were deep in a city that, strafed by two decades of

civil war, was already a paradigm of hell.

When it comes to portraying Hades, these days we do not hang about for

a Milton or a Dante. We wait only for television, a remorseless

manipulator and interpreter of our dreams, or in this case our

nightmares. And we do not have to wait long. This month comes Hostages, a co-production between

ITV’s Granada and America’s cable channel HBO. It is that most

controversial of genre hybrids, a docu-drama, detailing the captivity

of John McCarthy, Brian Keenan, Terry Waite, Tom Sutherland, Terry

Anderson and Frank Reed. Although it has been almost two years in the

making, it has beaten the hostages’ own accounts into the public

domain, and some, like Keenan and McCarthy, are unhappy. McCarthy has

said through his literary agent: ‘I am distressed that anyone should be

trying to portray my story when I haven’t been able to tell it myself.’

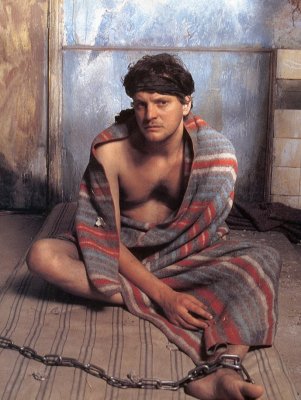

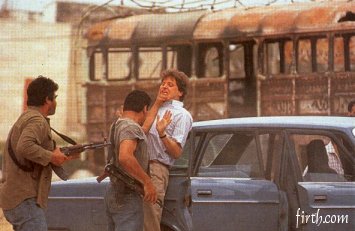

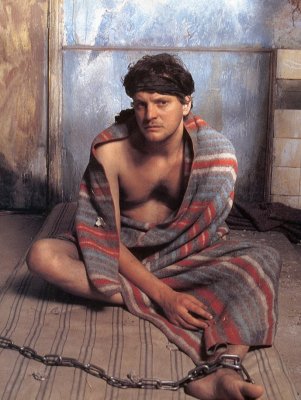

Colin Firth plays the young English television

journalist captured by Islamic terrorists and held for 1,943 days until

he emerged, seemingly unscarred, last summer. (His girlfriend Jill

Morrell will be played by Natasha Richardson.) My meeting with Colin

Firth is dominated by the amiable but insistent assertion that John

McCarthy is wrong. Colin Firth plays the young English television

journalist captured by Islamic terrorists and held for 1,943 days until

he emerged, seemingly unscarred, last summer. (His girlfriend Jill

Morrell will be played by Natasha Richardson.) My meeting with Colin

Firth is dominated by the amiable but insistent assertion that John

McCarthy is wrong.

‘I think if I was John McCarthy, a professional story-teller, I’d say

“hands off” too,’ he says. ‘I’d be amazed if he said anything else,

quite frankly. But people have got to be able to tell stories. The

professional storytellers of this world, be they journalists,

novelists, singers or actors, are always going to tell stories about

events which are provocative, inspiring, uncomfortable or capture the

imagination in some way—as this certainly does.’

Colin’s point is that since the hostage crisis was not something lived

through only by the hostages, its interpretation cannot be left

exclusively to them either. ‘It’s not just that you put yourself in

their place,’ he says. ‘It had a bizarre way of relating to things in

people’s lives. When you dig a bit, people compare experiences of their

own to being a hostage: the traps imposed by our own fears of daring,

of change, of losing people, our careers or our security.

‘I’m constantly going through my life wondering what my traps are,

wondering what I am choosing to do and what I am doing because I have

always done it—both in my career and personal life.’

He does not elaborate, but it becomes clear that Colin is almost

neurotically anxious not to be trapped, for example, by Hollywood. His

private life is not entirely his own. He lives in Hackney, east London,

but has a two-year-old son Billy who lives in Vancouver with Colin’s

former partner, actress Meg Tilly, whom he visits frequently.

We meet in London four weeks after Colin has completed Hostages. The 1988 BBC

drama-documentary Tumbledown,

in which he played Robert Lawrence, a career soldier crippled in the

Falklands, has just been repeated, but he is well-known anyway as the

clean-cut lead of A Month In The

Country and Valmont.

At 31, he has the sort of good looks designed by nature to fascinate

women more than men. Asked earlier if she minds Colin using her office

for the interview, a Granada press officer says she would quite happily

let him sit on her lap throughout.

Arriving slightly late, dressed in a baggy pink and grey T-shirt and

jeans, he does not look like a man who has returned from hell, although

some of the physical indignities he underwent during the filming sound

hellish enough.

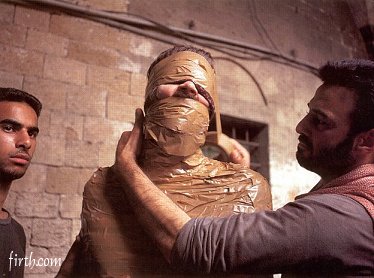

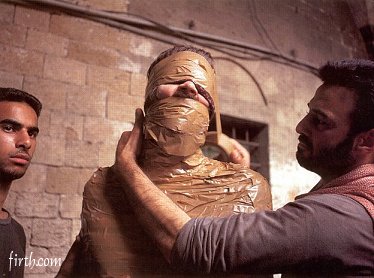

‘The hostages were

wrapped up like mummies in grey parcel tape from ankles to nose. They

were transported for eight hours like that in coffin-like drawers in a

lorry. It nearly killed them. Jean-Paul Kauffmann, the French hostage,

was there for more than 10 hours and asked them to kill him,’ he says.

‘It wasn’t until the tape was wrapped above my hands, which were by my

side, that I realised how trapped I was beginning to feel, and it

wasn’t till it got past my neck and chin that I realised it was going

to get even worse. It robs you of your physical sense of yourself...’

He breaks off, aware of how he might be sounding: ‘I know it always

sounds terribly precious when an actor talks like this. Someone has

been through this for five years and an actor does it for the cameras

and says, “Absolutely horrific, I must go into therapy.” But it gave me

a clue. And you apply your imagination, so you are not thinking about

going off and having a shower back at the hotel. You are thinking: what

would I be feeling now if it was for real?’

The magic of acting is to summon before an audience a life that has

normally never existed. The voodoo is more not less in conjuring one

that still does. Like everyone else, Colin had seen McCarthy on

television after his release, ironic, composed, exhilarated, speech

slurring from the drugs he had been given. But it was very little on

which to base a performance. The John McCarthy he plays is a product of

three imaginations: his own, director David Wheatley’s and writer

Bernard MacLaverty’s, all based on perceptions of a man they never met.

When Colin played Robert Lawrence in Tumbledown,

Lawrence was on set almost all the time. It had not always, he says,

been helpful. As it happens he feels slightly closer to McCarthy

because he can imagine himself being a journalist while he would almost

rather die than be a soldier.

Yet he has less in common with him than you might guess. McCarthy’s

public school sangfroid and undergraduate larkishness do not come

naturally to Colin, who is alternately defensively jokey and gravely

passionate over serious issues (over lunch later we plunge into

pacifism, Thatcherism, penal reform and the tabloids). Although he is

always playing public school types, he is a secondary modern boy who

failed the 11-plus and went to school in, rather than at,

Winchester—though programme notes sometimes fudge it. His education was

completed at drama school, not university. If he had been thrown into a

Lebanese cell, he would have brought with him a different set of

psychological and social baggage.

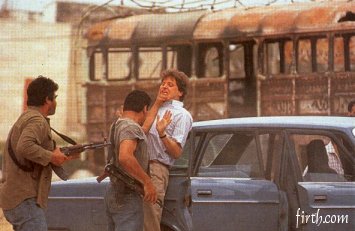

‘Quite frankly,’ he says of McCarthy’s captivity, ‘I

don’t think I would have been as brave.’ Nevertheless, in the film John

McCarthy, normally composed, breaks down at an early point. Stripped,

manacled, hit on the face by fist and rifle butt, he ‘freaks out’. On

another occasion he cracks after seeing cockroaches in his cell. The

scenes sound distressing to act and distressing to watch and remind me

of the only part of Tumbledown

that made me uneasy: where Lawrence is in bed with his former

girlfriend and loses control of his bowels. In the case of Tumbledown, however, the

justification was absolute, for Lawrence himself insisted that the

scene should stay. ‘Quite frankly,’ he says of McCarthy’s captivity, ‘I

don’t think I would have been as brave.’ Nevertheless, in the film John

McCarthy, normally composed, breaks down at an early point. Stripped,

manacled, hit on the face by fist and rifle butt, he ‘freaks out’. On

another occasion he cracks after seeing cockroaches in his cell. The

scenes sound distressing to act and distressing to watch and remind me

of the only part of Tumbledown

that made me uneasy: where Lawrence is in bed with his former

girlfriend and loses control of his bowels. In the case of Tumbledown, however, the

justification was absolute, for Lawrence himself insisted that the

scene should stay.

Portraying McCarthy’s hysteria, Colin says, does not impugn his

courage; it is the greatest bravery of all to be shaking and in tears

and still be polite and help others and to recover. Nevertheless, we

have no way of knowing if McCarthy will mind until after transmission.

The best we can say is that Granada believes McCarthy’s collapse did

actually happen. Alasdair Palmer, a former World In Action researcher who

worked on a previous docu-drama on Lockerbie, spent 18 months

researching Hostages before

handing over the facts for MacLaverty to do dramatise. He spoke to all

the hostages except Terry Anderson and Terry Waite, even briefly to

Keenan and McCarthy, and his major sources were Frank Reed and Tom

Sutherland. Granada’s press officer Barbara O’Brien, who for some

reason chaperons Colin during our discussion, insists every scene is

factual although dialogue has been invented.

‘I was very, very concerned when I found out that McCarthy wasn’t

endorsing it,’ Colin says. ‘I was very concerned they were making

something so soon after the event and if I hadn’t found myself

reconciled to it all in the end I wouldn’t have done it. I think the

script is honest and the only things that have irritated the shit out

of me so far have been the aspersions on the integrity of the people

involved.’

Hostages sounds promising. In place

of a facile TV-movie message about the indomitable human spirit, Colin

promises a focus on the ‘extraordinary nature of human

relationships—everything compressed into a little room: the dynamics,

the love, the rejections, the irritations. Someone described it as like

fives years’ enforced group therapy.’

He confesses, however, he has no real

idea of the programme will succeed. He is worried that much of the

humour, particularly between the Irish Keenan (‘a voice in the

wilderness character’) and McCarthy (‘the most popular boy in the

school’) was cut even before it could be shot. In the past he has been

unable to predict the reception his work will receive. A Month In The Country, bedeviled

by a wet English summer, felt like a disaster and yet it worked. Tumbledown, a film in which he

invested everything emotionally, disappointed him. He confesses, however, he has no real

idea of the programme will succeed. He is worried that much of the

humour, particularly between the Irish Keenan (‘a voice in the

wilderness character’) and McCarthy (‘the most popular boy in the

school’) was cut even before it could be shot. In the past he has been

unable to predict the reception his work will receive. A Month In The Country, bedeviled

by a wet English summer, felt like a disaster and yet it worked. Tumbledown, a film in which he

invested everything emotionally, disappointed him.

There is, nevertheless, one judgment on Hostages Colin will not be prepared

to accept: that of the real John McCarthy. ‘I couldn’t possibly afford

to,’ he says. ‘I know that he’s going to say it wasn’t like that, and

it won’t have been like that. But it’s some sort of ghost we are

raising, a dream image for our understanding of a shared experience,

just like the Falklands. I really don’t see this as pure entertainment.

It’s more like a need, a need to scratch an itch.’

Hostages will be shown

on ITV at the end of September.

|

Colin Firth plays the young English television

journalist captured by Islamic terrorists and held for 1,943 days until

he emerged, seemingly unscarred, last summer. (His girlfriend Jill

Morrell will be played by Natasha Richardson.) My meeting with Colin

Firth is dominated by the amiable but insistent assertion that John

McCarthy is wrong.

Colin Firth plays the young English television

journalist captured by Islamic terrorists and held for 1,943 days until

he emerged, seemingly unscarred, last summer. (His girlfriend Jill

Morrell will be played by Natasha Richardson.) My meeting with Colin

Firth is dominated by the amiable but insistent assertion that John

McCarthy is wrong.

‘Quite frankly,’ he says of McCarthy’s captivity, ‘I

don’t think I would have been as brave.’ Nevertheless, in the film John

McCarthy, normally composed, breaks down at an early point. Stripped,

manacled, hit on the face by fist and rifle butt, he ‘freaks out’. On

another occasion he cracks after seeing cockroaches in his cell. The

scenes sound distressing to act and distressing to watch and remind me

of the only part of

‘Quite frankly,’ he says of McCarthy’s captivity, ‘I

don’t think I would have been as brave.’ Nevertheless, in the film John

McCarthy, normally composed, breaks down at an early point. Stripped,

manacled, hit on the face by fist and rifle butt, he ‘freaks out’. On

another occasion he cracks after seeing cockroaches in his cell. The

scenes sound distressing to act and distressing to watch and remind me

of the only part of