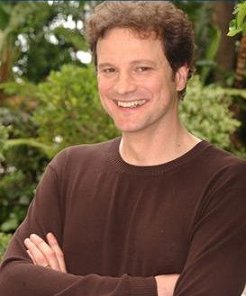

Whether he is the uptight suitor in "Bridget Jones's Diary," the half-mad cuckold in "The English Patient," or the simmering Mr. Darcy in TV's "Pride and Prejudice," love does funny things to people when Colin Firth is on screen. But playing the lover doesn't do much for Colin Firth. "I find no great joy in playing romantic characters or leading men," the 41-year-old Brit says firmly. "I find no great joy in trying to woo the audience. It's boring. For me, the fascination about being human lies in its difficulties." Like the stuffed-shirt types he fills out so well, Firth speaks with a drawing-room elegance that is both impeccably polite and confidently abrupt. The voice would be scary, if the face weren't so dimpled. And the discourse would be intimidating, if the man behind it wasn't so bent on making himself clear. As it turns out, the actor who's been called, "The Thinking Woman's Crumpet" is a thinker. And as Firth discusses a career that includes Oscar-winning blockbusters, art-film curios and at least one media sensation, he scatters quotable crumbs that never go quite where you'd expect. Take his new film. For his entry in the Summer Movie Sweepstakes, Firth journeys back to 1890s England for Oscar Wilde's "The Importance of Being Earnest." With a top-drawer cast that includes Rupert Everett, Judi Dench and Reese Witherspoon, and a witty adaptation by writer-director Oliver Parker, "Earnest" (opening May 31 in San Diego) is a pretty tropical fish that could get lost in a sea of cinematic sharks. But if you thought this was a good time to engage Firth in a battle against the Dummies of Summer, you would be wrong. "I love dumb movies," Firth said. "I think the cinema is a great place for mindless entertainment. It's not just a place of personal expansion and stimulation and education, thank God. It's the place where you go to be taken away somewhere. I think that's very important. I'm a great champion of triviality." Lounging on a hotel couch in jeans, a plain brown sweater and sneakers, the surprisingly boyish Firth could pass for a regular guy on his way to an "Attack of the Clones" matinee. But beginning with his film debut in 1984's "Another Country," the son of two liberal-minded teachers and the grandson of missionaries has spent much of his time playing stuffy prigs and slow-boiling headcases. From the pompous Lord Wessex in "Shakespeare in Love," to the homicidal introvert in "Apartment Zero" and last year's Emmy-nominated turn as an anti-Semitic lawyer in HBO's "Conspiracy," Firth is often the man least likely to be liked. But when he played one of literature's most uptight gentlemen, a nation went just a little bit nuts. The film was "Pride and Prejudice," a 1995 BBC miniseries based on Jane Austen's beloved novel. As the very rich, very proper Mr. Darcy, Firth was snobby, imposing, vain and distant. But when he fell in love with the feisty Elizabeth Bennett (the wonderful Jennifer Ehle), the brooding Darcy melted in the most stirring way. By the end of the six-part series, the BBC had a huge hit on its hands, and a busy character actor had become a full-fledged sex symbol. "My country became a different place for me," Firth says of the flurry of press, gossip and Darcymania that followed. "I was delighted that it was happening, but it took me so by surprise, I couldn't really make sense of it. I had never focused on playing romantic characters, so I actually felt like it was happening to someone else, and I did not know how to answer for it. "When people asked me about the experience, I tended to sidestep it. And immediately that became identified as an attempt to shun it. I became, 'The Reluctant Heartthrob.' It's not that I hated it. I just didn't feel like I owned it." Never the most savvy careerist, Firth did not follow his Darcy triumph with a fleet of celluloid dreamboats. Instead, he devoted himself to fiber-rich BBC roles ("Donovan Quick," the "Nostromo" miniseries) and quirky art-house films ("Fever Pitch," "My Life So Far"). Then along came Ms. Jones. Like most British women (and the Americans who caught the hugely popular A&E airing in 1996), "Bridget Jones's Diary" author Helen Fielding had a "Pride and Prejudice" fixation. So much so, that she based the pompously attractive Mark Darcy character on Firth's version of Mr. Darcy. When the book became a movie, Firth became the 21st-century version of his 19th-century snob. Once again, he was playing a prickly, difficult man, and once again women on either side of the screen were dropping like flies. "I haven't ever seen an actor who generates the excitement, especially from females, that Colin does," says Donald Haber, executive director of the Los Angeles branch of the British Academy of Film and Television Arts. "He transcends his technical expertise by being so very appealing. He's not just carrying his role, he is adding warmth. I think over the next 10 years, he is going to become a very major star." Meanwhile, the man behind the buzz just shakes his head. "I do not understand it," Firth says, looking convincingly baffled. "As a man, I don't dare to venture a theory as to what makes women so attracted to these characters. But I do think there must be something appealing about a powerful, forbidding figure who becomes warm and loving. That's about as far as I dare go." And that's as far as he needs to go. While it is true that Firth is a handsome man and a first-rate smolderer, women fall for his difficult heroes for the same reason he does. Because they are complicated and conflicted. Because they are stubborn and principled. Because when you truly win them over, you have truly won. "I turned down Mr. Darcy several times. And then a very literate friend said I had to do it, because no one was capable of being as unashamedly unpleasant and unsympathetic as I was. And that was the hook for me. I wanted to engage with his difficulties. He was emotionally impeded, and that's what I was going for with that performance. I just said, 'Here I am, to hell with the rest of you. Hate me if you must. I don't care.' "I enjoyed the honesty of that," Firth says, settling back with his bottled water. "I enjoy the fact that you can sometimes be more honest with that acting mask on than you can at any other time in your life." Firthomania!

"You would think that at a certain point, everyone who was going to get excited about Colin Firth would have done it," Haber says with a chuckle. "But every time we have a Q&A with him, we have more people wanting to come. It is quite comical sometimes the length they will go to get into the theater. All great actors have people who really follow their careers and enjoy their performances, but Colin somehow touches a deeper nerve. It isn't just a fan club, it's an emotional fan club." Obviously, Firth's fans admire his intelligent, oddball movies. But because they read that he is a devoted husband and father, a dedicated political activist and a lover of difficult novels, they admire him, too. And Firth is not sure that's such a good idea. "I get letters from people who think they've got an understanding of what sort of person I am, but it's actually a montage of snippets from interviews and the kinds of things I've chosen to say in public. People want to create an image for the human being behind the part, but that image is not recognizable to me or anybody who knows me." "I have no problem with it," he adds with an amiable shrug. "But I think it makes much more sense to piece clues together by looking at someone's work." For those of you who are keeping track, the next clue drops in the fall. In the bittersweet comedy "Hope Springs," Firth plays Colin Ware, an awkward British artist who takes an impulsive trip to the United States after being dumped by his girlfriend. Minnie Driver is the acid-tongued ex, Heather Graham is the sweetly dippy new love interest, and Firth is the man in the middle. The one whose bruised silences speak volumes. "Outsiders have always been a bit of a leitmotif in my work," Firth says, that rich voice rising smoothly above the lobby Muzak. "And it isn't an accident of typecasting that repression comes up a great deal. I'm always interested in what happens to people when they're stifled and limited in some way. Watching people try to contain tears is often far more moving than watching somebody's body fluids exploding all over the screen." |

For

an actor who has yet to carry a major motion picture on his own, Firth

has a rabid and well-heeled female following. They buy his used

pillowcases

and gently worn sweaters at charity auctions. They attend his talks on

behalf of those seeking political asylum. Earlier this month, some fans

trekked down from Seattle and Portland for BAFTA/L.A.'s screening of

"Earnest"

and the question-and-answer session that followed.

For

an actor who has yet to carry a major motion picture on his own, Firth

has a rabid and well-heeled female following. They buy his used

pillowcases

and gently worn sweaters at charity auctions. They attend his talks on

behalf of those seeking political asylum. Earlier this month, some fans

trekked down from Seattle and Portland for BAFTA/L.A.'s screening of

"Earnest"

and the question-and-answer session that followed.