But in the end, the role he is likely to be best remembered for is the brooding Mr. Darcy in a BBC production of Jane Austen's "Pride and Prejudice." That lavish 1995 miniseries, broadcast here on A&E and seen by more than 100 million viewers worldwide, turned Firth into an unlikely international heartthrob and produced a vast following of amorous female fans. Firth's not all that handsome—his neutral actor's face can be substantially altered by expression and makeup—but having a crush on Colin has become a pop-culture commonplace. The Darcymania has been a mixed blessing for Firth, whose aspirations as an actor extend beyond umpteen hours spent smoldering in mutton-chop whiskers. Greater celebrity translates into better roles. But the enduring magnetism of Darcy—whom Firth once referred to as "a bizarre doppelganger that I've spawned"—somehow seems to take away from his other accomplishments. Here at the Essex House Hotel, Firth has just finished a series of round-table interviews to promote "The Importance of Being Earnest." He stars as Jack Worthing, a gentleman who escapes the tedium of his country life with the assistance of an invented brother, Ernest. During the interviews, the most common question did not concern Wilde, Jack Worthing, or even Ernest Worthing. Nor did it involve Firth's co-stars in the film: Rupert Everett as the irrepressible Algernon Moncrieff, along with Reese Witherspoon, Tom Wilkinson and Judi Dench. The journalists asked about Mr. Darcy. "Some people do it with irony and humor. Some people do it earnestly. Some people are ashamed of having to ask the question," says Firth. "And every so often there will be a journalist from Swaziland who doesn't know anything about it—wonderful."

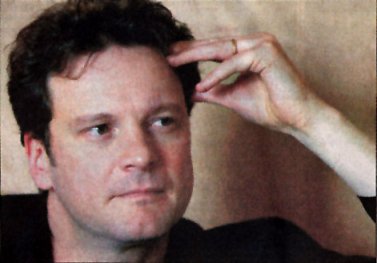

A Lot Under the Surface Firth, 41, isn't fond of giving interviews, and as he speaks, his arms rarely remain still. Again and again, he begins to cross them, and they hover in an almost-crossed position. Then, perhaps not wanting to seem unfriendly, he deliberately uncrosses them. "I'm not particularly comfortable being encouraged to give things away about myself," he says. "I don't think I'm unusual in that. I do have certain questions about what one can really say. My personal life's nobody's business; I'm not unusual in that, either. My views on world politics and the rest aren't really of interest to anybody, particularly; they're not relevant. "And talking about the work is difficult because it's the kind of work that is hard to talk about. It's hard to analyze it and it's hard to say anything sensible about it. . . . So I do find that I'm in a position where I'm doing more to mask than to reveal." Directors who have worked with Firth praise his depth. Oliver Parker, who helmed and wrote the screenplay for "The Importance of Being Earnest," says that Jack—perhaps the least witty of the play's characters—often turns out to be merely a foil for the other players. "I framed this adaptation in a way that Jack was central to the emotional narrative," says Parker. "So I was looking for somebody who has a certain sympathetic quality, who could be at once vulnerable and complex. And Colin, I think, is very skillful at creating an active inner life while sustaining the comedic requirements of the piece." Firth prefers to play characters who have a lot going on beneath the surface. "For obvious reasons I tend to do films about English people, and one of the defining features of English people—at least in the mythology we have of English people—is emotional repression," he says. "I do think that very often what is not revealed is more interesting than what is revealed explicitly. "One of the great things about the art of writing when it's good is that it expresses the difficulty of communication," he explains. "The moment you most want to pour your heart out is often the moment you're most stuck for words. I find those moments and those limitations very interesting." Firth learned his craft at London's prestigious Drama Centre, where he played Hamlet and King Lear (he describes the latter as "a hideous embarrassment"). He learned the dangers of overplaying an emotion, and the benefits of making a character credible. "Watch Rupert Everett in 'The Importance of Being Earnest,' and you almost get the sense that he's having to repress his mischief," Firth says. "He's not trying to be mischievous. That's why he's so believable— you get the idea if you let this guy off the leash, he'd be even more outrageous." Firth made his film debut in 1984, playing opposite Everett in an adaptation of Julian Mitchell's play "Another Country." Firth's character was an angry young misfit, an embittered communist trapped in a posh English boarding school. Since then, the actor has chosen a variety of parts, mostly a combination of leading roles in small, interesting films and supporting parts in more mainstream projects. If there's a common link between his characters, it's that they are all outsiders in one way or another. His stammering Tom Birkin in "A Month in the Country," traumatized by the carnage in the trenches of World War I, could relate to no one except the wife of the local vicar. In the political thriller "Apartment Zero," he portrayed a film buff who slowly loses his sanity. Firth played the title role in Milos Forman's 1989 "Valmont," which was largely ignored in favor of the previous year's "Dangerous Liaisons"; his malevolently charming Valmont operated just outside French society. Firth suspects that he's drawn to outsider roles because of his unusual upbringing. Firth's grandparents on both sides were missionaries in India, where both of his parents were raised. His parents were academics, and the family spent the first four years of his life in Nigeria. After that they moved around England for several years, then spent a year in St. Louis before returning to England. "I am an outsider. I have always been. I'm not lamenting that fact. It does create confusion, and it is a little painful . . . but I think it's been enormously beneficial to me," he says. "I've never come from the place I've lived in. I've always been identified with the last place I came from. When I was in school in America, I was the Englishman, and then I came back and I was nicknamed the Yank. "In school I was the only one whose parents had this kind of multicultural background," he says. "I rather reveled in it to some extent. . . . I suppose I got into feeling a little bit different. . . . I saw other perspectives. "It must be there in the way I choose roles. We don't have much control, actors, in terms of what we do. We don't write the material. We don't have the perfect choice of what's available. But I think I've veered toward that." In 1997, an alarmingly lumpy Firth starred in "Fever Pitch," the film version of British writer Nick Hornby's confessional book about his obsession with the Arsenal soccer team. Firth says that even though he isn't much of a soccer fan, he identified "enormously" with Hornby's book. "I just felt he was describing me. He solved his problems with soccer, and I guess I became an actor and played outsiders." The friendship between Hornby and Firth continued after "Fever Pitch," and two years ago Hornby, whose son has autism, edited "Speaking With the Angel," a collection of short stories benefiting educational programs for autistic children. Participating authors included Roddy Doyle, Irvine Welsh, Dave Eggers and Helen Fielding. Hornby invited Firth to contribute a story. "He had often talked to me about writing," recalls Hornby. "He was right on the edge and he just needed a finger to make him jump. I thought he'd be a good writer—he's smart—and that there would be interest. I thought, you can make my charity a few quid . . . and we could do each other a favor." Firth's story, "The Department of Nothing," is a lot better than one might expect from a movie star with literary aspirations. In it, a lonely 11-year-old finds solace in the fantasy stories told to him by his beloved, dying grandmother. "I was almost hoping that my story wouldn't make the collection, to be honest," says Firth, but he's not being honest at all. He uncrosses his arms. "If you want to know what I was really hoping, I was hoping it would be brilliant, that it would be great and hold its own fantastically or even be the best of all of them, and that I'd be discovered, and a new literary star is born." Hornby estimates that "Speaking With the Angel" earned half a million dollars for its charities. Probably $450,000 of that, he says, came from Firth fans.  Jane Austen's Fitzwilliam Darcy may be the most crush-worthy bachelor in all of English literature, so perhaps Firth should have expected to collect a few admirers with "Pride and Prejudice." But he was unprepared for the panting hordes. The Guardian hailed him as "our national treasure." The British tabloids scrutinized his brief relationship with co-star Jennifer Ehle (who played Elizabeth Bennet, naturally), and hounded him relentlessly even after it was over. (The Sunday Mirror once ran a photo of him bringing home a new vacuum cleaner. Caption: "Mr. Darcy does the household chores.") Then there was the proliferation of fan Web sites—Firthfrenzy.com, afirthionado.com—and fan clubs that include Friends of Firth and The Darcy Lunatics. For the rest of us, the most enjoyable aspect of Darcymania can be found in Helen Fielding's "Bridget Jones" books. In the first one, hapless "singleton" Bridget obsesses over Darcy and Elizabeth and falls in love with a contemporary version of Darcy, a human-rights lawyer named Mark Darcy. In the second novel, aspiring journalist Bridget interviews Colin Firth for the Independent. But she is unable to control her lust, and the Q&A comes to an unfortunate end when she lunges for the actor. "I was delighted to become a popular-culture reference point. I'm still delighted about it actually, and I still find it to be weird," says Firth. "For the books to be these huge bestsellers has probably done as much to burn my name into people's minds as much as anything I've ever done, really." This is how pop culture feeds on itself: When the film version of "Bridget Jones's Diary" was made, Firth played Mark Darcy. Even if "Bridget Jones" didn't conflate Colin Firth, Mr. Darcy and Mark Darcy, some people would still have a hard time differentiating among the three. Carrie Gardiner, a Rhode Island elementary school art teacher and grandmother who is webmaster of the firthfrenzy.com Web site, says she feels a special connection to Firth and both of the Darcys. "We feel for Colin," she explains. "You want Mark Darcy to win Bridget. You feel embarrassed for Mr. Darcy when Elizabeth refuses him. This once-proud Darcy is feeling embarrassed, awkward, vulnerable, and your heart just goes out to him." Director Oliver Parker compares Firth to vintage Hollywood stars like Henry Fonda and Jimmy Stewart. "Colin conveys a quiet reserve and strength of character. There's a natural humility matched with intelligence and wit to sustain the persona that appears onscreen," says Parker. "The more time you spend with him onscreen, the more interested in him you become." But for someone who inspires such adulation, Firth is remarkably adept at portraying unattractive characters. In "The English Patient," he played the chubby obligatory husband of the Kristin Scott Thomas character; how could we blame her for cheating on him with Ralph Fiennes's handsome explorer? Two years later, in 1998's "Shakespeare in Love," Firth's mean-spirited aristocrat Lord Wessex—"the opposite of everything that film celebrates," says Firth—lost out to another Fiennes brother, Joseph, who played the love-struck Will Shakespeare. "I think Colin's actually interested in acting," says Hornby. "I know that sounds like a stupid thing to say, but what I know of a lot of actors is that they're more interested in being film stars. A lot of actors wouldn't have done that part in 'The English Patient.' " Unlike Firth, who is married to an Italian film producer, Fitzwilliam Darcy is eminently eligible. After "Pride and Prejudice," Firth received a number of letters suggesting that Mr. Darcy's attraction goes deeper than sexual and romantic appeal. "The letters were from women of a certain age, who said that in some profound way, I had reminded of them of their dead father," he says. Firth began to wonder whether Darcy provided a kind of reassuring presence for women who deeply missed someone. But maybe there's another type of worship entangled in there. Firth once got a letter from a Swiss psychologist who wrote that there's some of the Old Testament God in Mr. Darcy. "Her interpretation was that there was almost a religious archetype that goes on the trajectory from the unforgiving, judgmental God that's going to reject and punish, to actually being benevolent and loving and generous." "Whatever way you look at it, I think that story does make him sort of irresistible," he says. "I read that book, and I fell in love with him." |